It’s become a habit of mine, before visiting a new country or a new city, to pick up a copy of a book from that place from the library and get immersed in it before I even get there. I don’t know that it necessarily helps with my immersion once I arrive – after all, often, these books come from a completely different time period (or a fantasy genre), meaning that I show up in Germany expecting Goethe only to encounter modern Berlin. But for better or for worse, it’s become part of my pre-trip ritual, and I don’t see myself stopping any time soon.

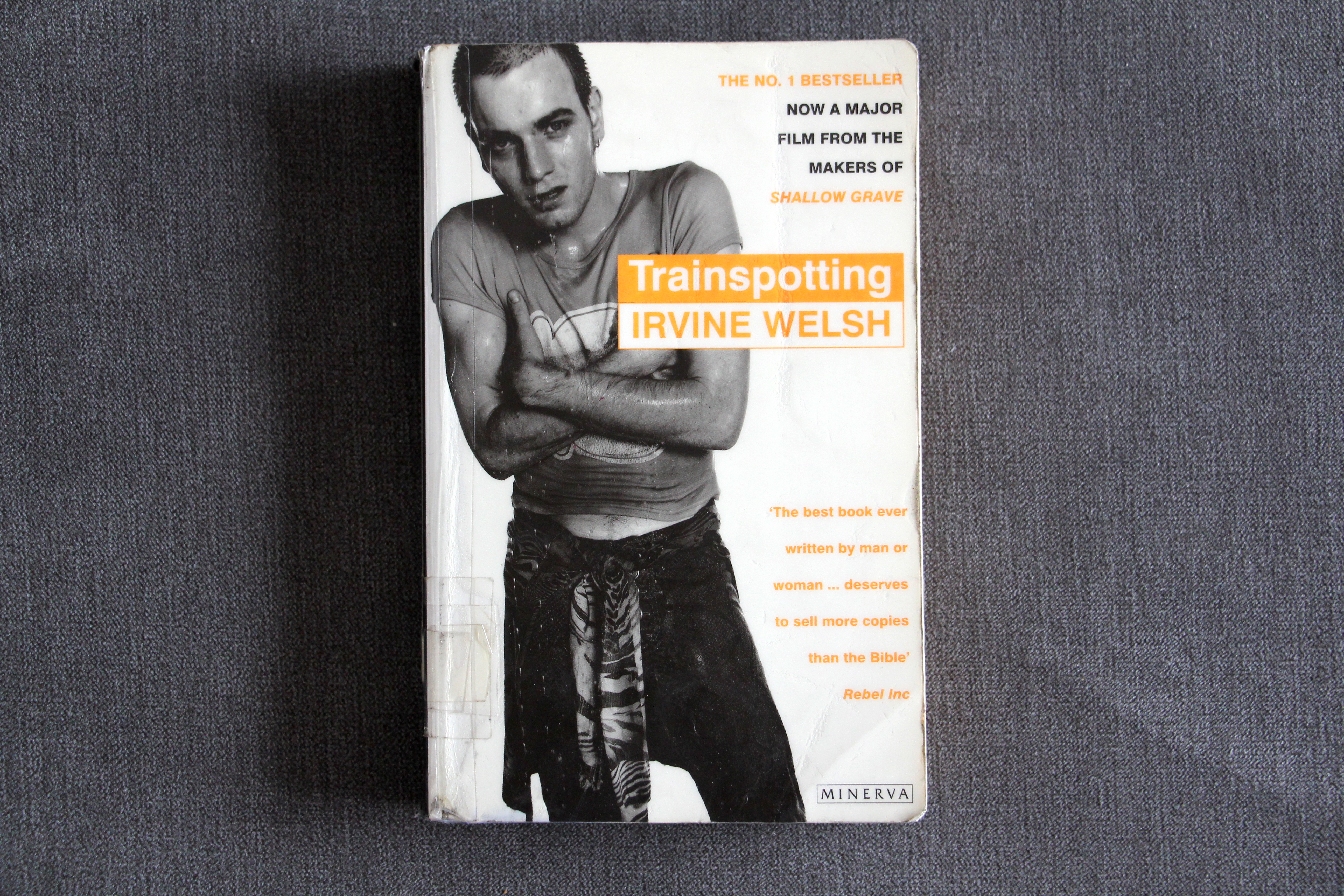

In the days leading up to my trip to Scotland with The Country Boy, I opted for Trainspotting, a book I had been intending to read for years, ever since falling in love with the film adaptation in college. Of course, I knew (or at least I hoped) that the ramshackle group of junkies and drunks wouldn’t be reflective of our trip (and of course, it was not), but what I didn’t expect was how much the musicality of the language would be.

Trainspotting is less of a novel and more a set of interlinked vignettes or stories, told from alternating points of view from different members of a close friend group. The true mastery here, in my mind, is the use of language: the entire book is written with a Scottish accent, and what’s more, even to the untrained ear, the differences in speech, pronunciation, and intonation from character to character are evident on the page.

I’ve always had a tough time with written accents; often they’re done poorly and only in the dialogue of one character. They become distracting, more a nuisance than anything else – a sort of lazy man’s dialogue tag. But perhaps because this book is written entirely in an accent, the voice of the book seems to become a synonym for the setting and for the ties that bind all of these disparate characters, and the nuances from one character’s way of speaking to another are evocative of their individual differences – much in the way voice reflects differences between people in real life.

While the omnipresence of the accent meant that occasionally, I had to slow down and read a paragraph over again, just to make sure I’d understood it (I’ve never read the words bairn (child) or fae (from) before), Irvine Welsh’s mastery of story and character make it easy for even a non-Scott to become immersed in the musicality of his text.