“C’est l’histoire d’un garçon mélancolique parce qu’il a grandi dans un pays suicidé. C’est l’histoire d’un pays qui a réussi à perdre deux guerres en faisant croire qu’il les avait gagnées, et ensuite à perdre son empire colonial en faisant comme si cela ne changeait rien à son importance. C’est l’histoire d’une humanité nouvelle, ou comment des catholiques monarchistes sont devenus des capitalistes mondialisés.”

РFr̩d̩ric Beigbeder, Un Roman francais

I was warned, when I started writing my thesis–currently a 22-some-odd page of drivel, outline, and, OK, some well-written French–that I would soon begin to eat, sleep and live my topic.

Poppycock, said I, for when I talk to myself, I often use outdated words that no one else uses. (Why not? No one’s making fun of me in my own head… they know me here.) I chose my topic somewhat flippantly; I didn’t expect I would have to choose so soon, so I spat out the first thing I knew two sentences about it, and my tutrice scribbled it down, and there it was. My topic. Equality in novels between the literature of 1848 and today. I didn’t think it would ever be any more than one more thesis statement of one more paper I would turn in and quickly forget about.

My father will attest to the fact that I’m bad at being warned. I never take it seriously… so as I slowly delved into my corpus–a hefty bundle of several thousand pages of French literature–I didn’t even notice how much it was taking over my life.

“Je me trouve fort à l’aise sous ma flétrissure,” écrit Baudelaire à Hugo après l’interdiction des Fleurs de Mal. I had to look up flétrissure–it means dishonnor and comes from a botanical metaphor–but I was less interested in what the sentence actually meant and more concerned with the fact that I was overcome with the feeling that Victor Hugo and Charles Baudelaire were cheating on me with one another.

Yes, I am aware that this is a strange feeling to have, but it makes it no less real, when I consider the connections I have to the works of both writers–Baudelaire’s “Anywhere out of this World” that can take at leas 65% of the credit for my final decision to move to France (Je pense que je serais toujours bien là ou je ne suis pas…), Hugo’s Les Misérables, which I have seen and studied in every version, from the musical on Broadway that my parents saw just days before I was born to the epic made-for-television masterpiece starring Gérard Dépardieu and the not-so-masterpiece even with Geoffrey Rush and Liam Neeson.

I’m reading Les Misérables in its original French for the first time for my thesis, and I’m feeling a growing kinship with the French poor of the 19th century… strange, considering that my own ancestors were still somewhere between Sicily and Ireland at that point. Even more, however, I find myself relating with the complaints of 40-some-odd Frenchmen. Not too strange, as I often identify with male writers from that generation, but it’s the French part that I find so disconcerting. After all, we’re talking about a discontented French descendent of the haute bourgeoisie, a person who is at arms with his country and everything it stands for, a country I’m still clinging onto with my fingertips in hope that one misstep with the infamous bureaucracy won’t send me tumbling back to the homeland.

And yet there are points made in Un Roman français, a work by Frédéric Beigbeder (the mind behind 99 Francs starring Jean DuJardin, for those of you who like offbeat modern French cinema) that I can’t help but agree with. “La France étant une nation amnésique, mon absence de mémoire est la preuve irréfutable de ma nationalité,” he says: France being an amnesiac nation, my lack of memory is the irrefutable proof of my nationality. An amnesiac nation, une nation amésique. I love that.

I want France to be my country in the way that it is for people who are born here: just something you have, something you can take for granted, instead of what it is for me: a place I crave but a place that eludes me, for whatever reason. I’m always learning more about it; I soak it up all the time, absorbing my surroundings as best I can. The pictures are the Country Boy’s cousin’s small village covered in snow. For her, it’s life; for me, it’s mystery and gorgeous. I want it to be as normal and natural for me as my own backyard, but I know that no matter how long I stay here, I’ll always be American. I don’t want to lose that part of myself, but it’s nice to forget, as I delve into literature on the métro and slowly let my English fade away, that Frédéric Beigbeder’s bitter ownership of the country I love is mine.

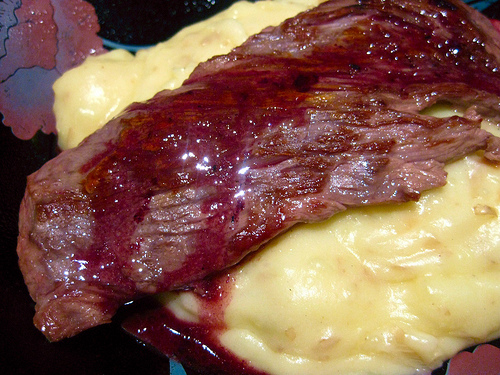

Steak with Beurre Rouge and Aligot with Comté

For the steak:

2 bavette steaks, room temperature (about 4 oz. each)

1 tsp. salt

1 tbsp. vegetable oil

1 tsp. butter

For the sauce:

1 cup red wine

1 tbsp. butter

For the aligot:

200 g. (7 ounces) potatoes (peel if you like; I’m lazy and leave the skins on in a conspicuously un-French manner)

1 clove garlic, peeled

1.5 tbsp. butter

70 g. (2 oz.) shredded Comté cheese

1 tsp. black pepper

salt to taste

While your steaks are coming to room temperature, put the potatoes and garlic in a pot and cover by about two inches with cold water. Bring to a boil over high heat, then cook for about 20 minutes, until tender.

When the potatoes are about 5 minutes from being done, heat a heavy skillet over a high flame (and turn on the fan/open the windows!) Salt the steaks on both sides, and heat the butter and oil. When the butter melts, place the steaks in the pan and allow to cook, without moving, for 2 minutes. Flip and cook on the other side for 2 minutes. For medium-rare, remove the steaks now, cover with foil and allow to rest.

Reduce the heat under the pan to medium and deglaze with red wine. Allow to cook about 5 minutes while you prepare the potatoes.

Drain the potatoes and garlic and return to their pot. Using an immersion blender, purée them until smooth. With a wooden spoon, beat the Comté and butter in until melted and smooth. Add the black pepper and salt to taste (you won’t need much with the cheese).

Turn the burner off under the sauce and stir in the tablespoon of butter.

To serve, divide the potatoes between two plates and place the steaks on top. Stir any accumulated juices from where the steaks were resting into the sauce, then drizzle a bit on each steak. The rest can be served on the side.

1. “For her, it’s life; for me, it’s mystery and gorgeous.”

Equally true with you in the third-person position and pretty much anyone you know in the first. As you point out, “Je pense que je serais toujours bien là ou je ne suis pas…”

2. Sure, the recent Les Mis film adaptation was not the best thing ever… but Claire Danes was in it, and she is hot.

Sorry, not the most sophisticated thing ever to say. Let me redeem myself.

I last read Les Miserables in English at age 15 (back when I couldn’t have recognized the name Victor Hugo when spoken in French), and skipped most of the section about argot and bits of other history that I’m sure would now be much more interesting to me. As soon as I dig myself out of the early modernists, I’m inspired to plunge back into some Hugo…

3. That food looks AMAZING and I want some right this minute.

I use an immersion blender nearly every day in my kitchen… it’s a great tool!