When I was in high school, I read a lot of books by wayward men, about wayward men.

It’s common knowledge, now, that our American writing cannon is far from diverse. I can’t fully fault my school, which had me reading Toni Morrison and Mary Karr with the same fervor as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Joseph Conrad, but in my own reading, engulfed in the desire to be reading “the classics,” I cast aside all manner of delicious writing to read the sort of meandering, navel-gazing male narrative that seemed defined by an experience of middle age that I had never experienced, would never experience, but that had, for some reason, been earmarked as must-read literature.

***

I have a friend who has a child; the child must be about ten now (what a terrifying thought), but when I first met her, she was three, and I remember watching, captivated, as she tapped on the page of a picture book in an attempt to “zoom in.”

When I was a small child, long before smartphones, I was reading a picture book in kindergarten – a book about the fight for civil rights – and I tried to tilt it to look beyond what was depicted in the crowd scene.

When I noticed my error, I was embarrassed, even though I was alone.

***

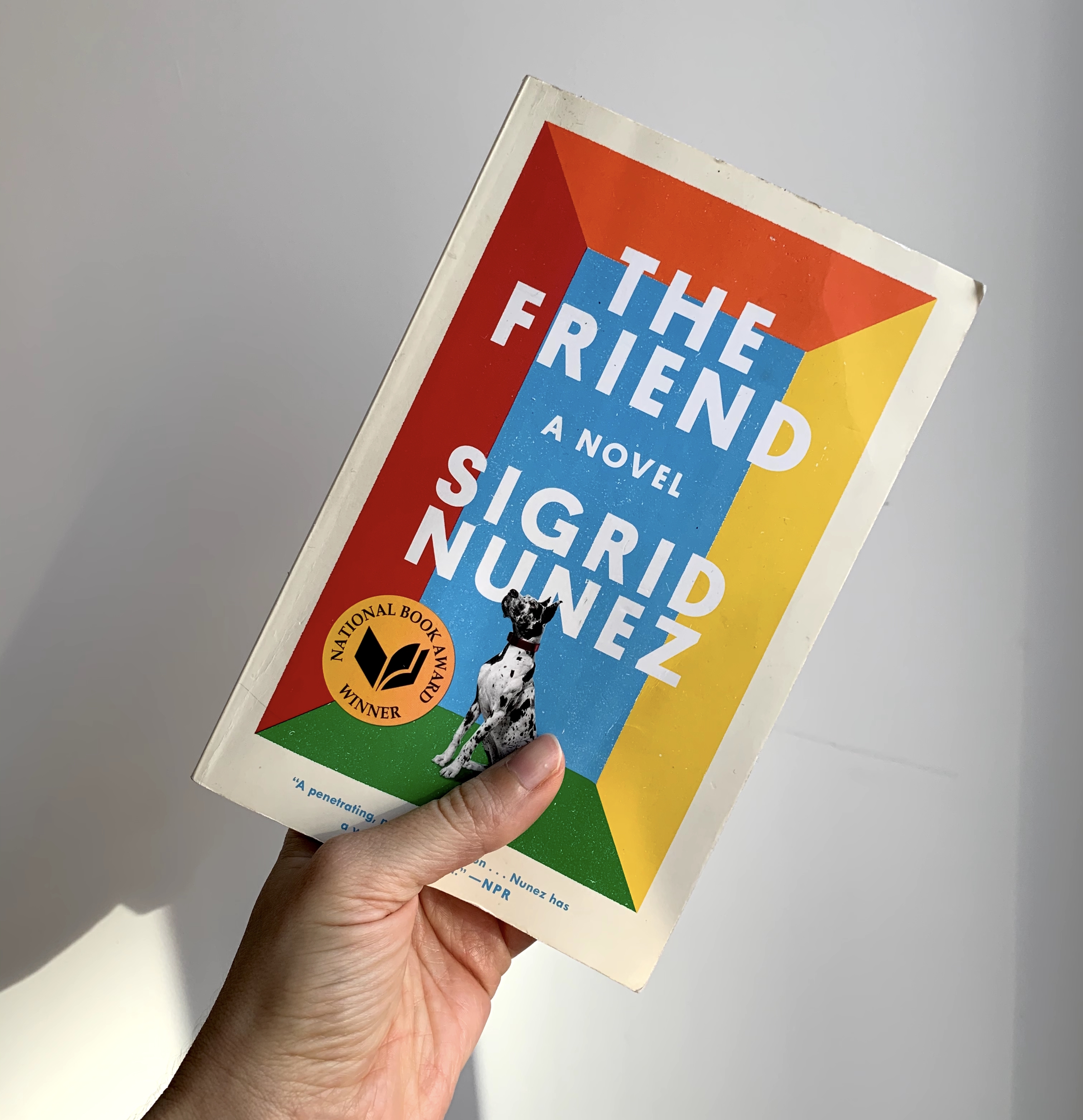

Reading The Friend feels a bit like tilting your head into the crowd scene of a male narrative, seeing how someone else perceives the self-centered womanizer trope appearing again and again in the cannon of great literature – not just American, but French, too. In Sigrid Nunez’s book, a woman mourns the death of her long-time best friend, skirting his three ex-wives (who, to varying degrees, have treated her with something ranging from suspicion to downright loathing) to recuperate his Great Dane, which he has left her in his will. Her management of the dog is her way of grieving the loss of this person, a clear picture of whom we only glean towards the end of the book.

Why does this woman love this man so much? Is it just his intellect, as it seems on the page, or is there something more? Is there something of the unconditional, overwhelming love she finally gains from the dog, in the relationship she’s lost?

The book leaves us with so many unanswered questions, but that isn’t a bad thing. It’s an appraisal of various kinds of love, none of which is the kind one usually focuses on, in a novel: gone is the treatise of romance and sexual passion. Instead, we see this woman mourning a shadow person, enveloped in the unconditional love of a canine. We see an unnamed background character grant her the sort of favor that might point to – or lead to – love of a different kind, but this is not that book. Our protagonist, so overwhelmed by grief, can barely see the kindness in it.

This is a story about a woman and a dog… but it is so much more than that.