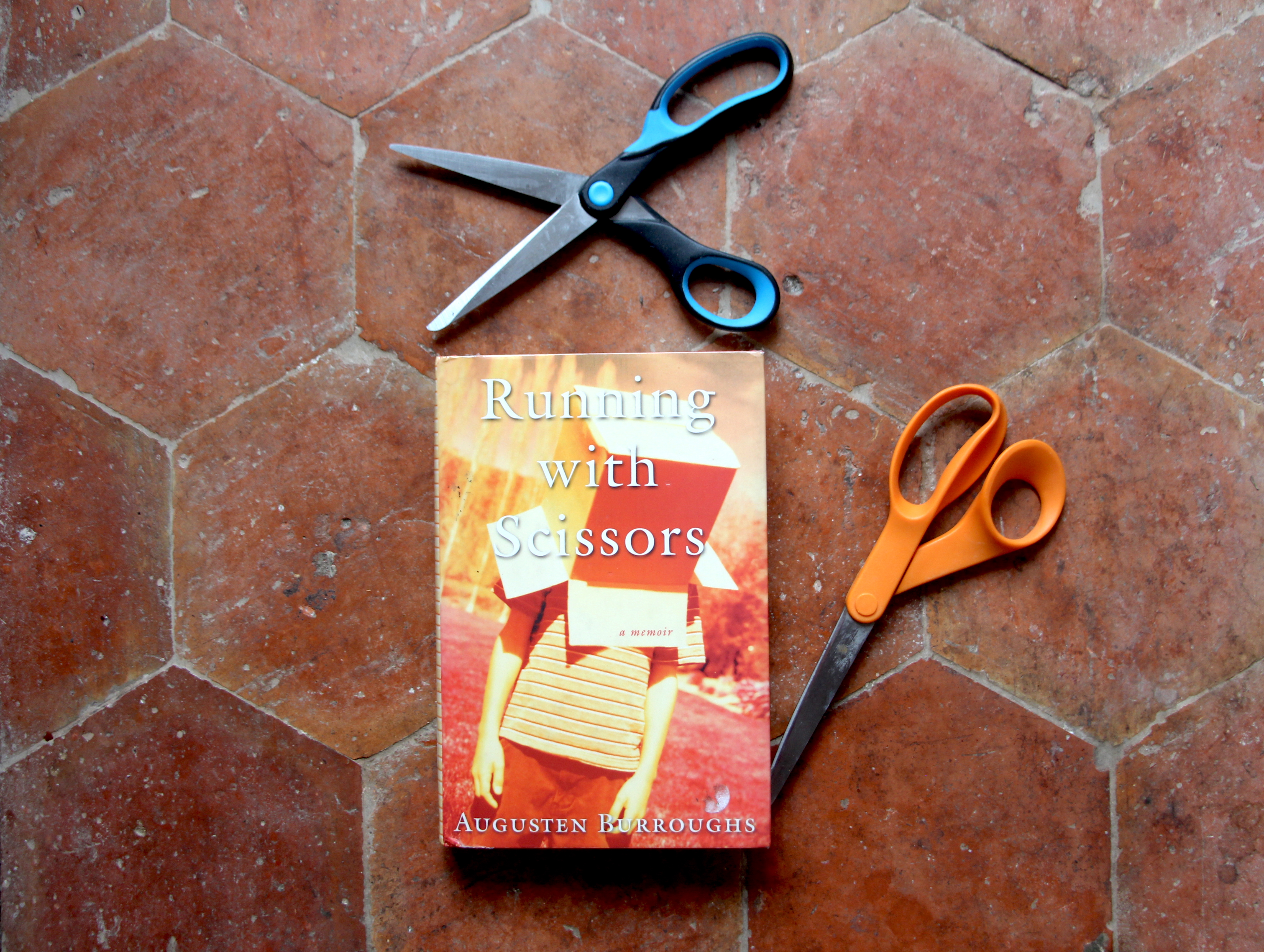

My senior year of high school, I took a playwriting seminar as my English requirement. In addition to debating whether the word should be playwrighting or playwriting, I remember discussing the idea of truth being stranger than fiction, the fact that just because something happened didn’t mean it was believable in a story. But in Augusten Burroughs doesn’t stand on the ceremony of fiction – or even auto-fiction – in his “memoir” Running with Scissors, dubbed a “book” for legal reasons to protect the (not so) innocent.

I know I’m a latecomer to the genius of Burroughs, but when I finally opened the shiny cover of this book, I devoured it in a matter of hours. With an incredibly wrought wry distance, Burroughs unveils and divulges the oddness of his childhood: one governed by abuse and estrangement and abandonment, but also love and hope and kinship of many kinds. The anecdotes he conveys are each stranger than the next: a psychiatrist who believes God is talking to him through his bowel movements; a bored Augusten and his adoptive sister Natalie tearing down the kitchen ceiling just to see the sky. It’s engrossing reading, beautifully captured in sparse, direct prose.

While when one steps back from the actual events in the book, it’s with a sort of abject horror, Burroughs himself manages to find – and convey – the humor in the very, very odd set of circumstances that defined his childhood. And it’s this humor – with a touch of compassion – that makes this book such a marvelous read.