I know I’m not the only writer who avoids reading similar books to the ones that she is working on. I have a good friend who stays away from books about the same time period she’s writing in, another who tries to avoid reading stories set in the same city she’s writing about.

There are a lot of reasons for doing it: maybe you’re afraid of becoming derivative; maybe you’re just scared that you’ll feel, in that time when you’re so sensitive about what you’re doing, that someone else is doing the same thing as you are, but better.

I know that I’m guilty of this: a fellow Parisian came out with a book about a girl’s childhood in a French village, and I purposefully ignored it, even though I was excited to read it, because I didn’t want it to taint my own work, my own experience.

I thought that I was doing the right thing by picking up a book of short stories. Oh man, was I wrong.

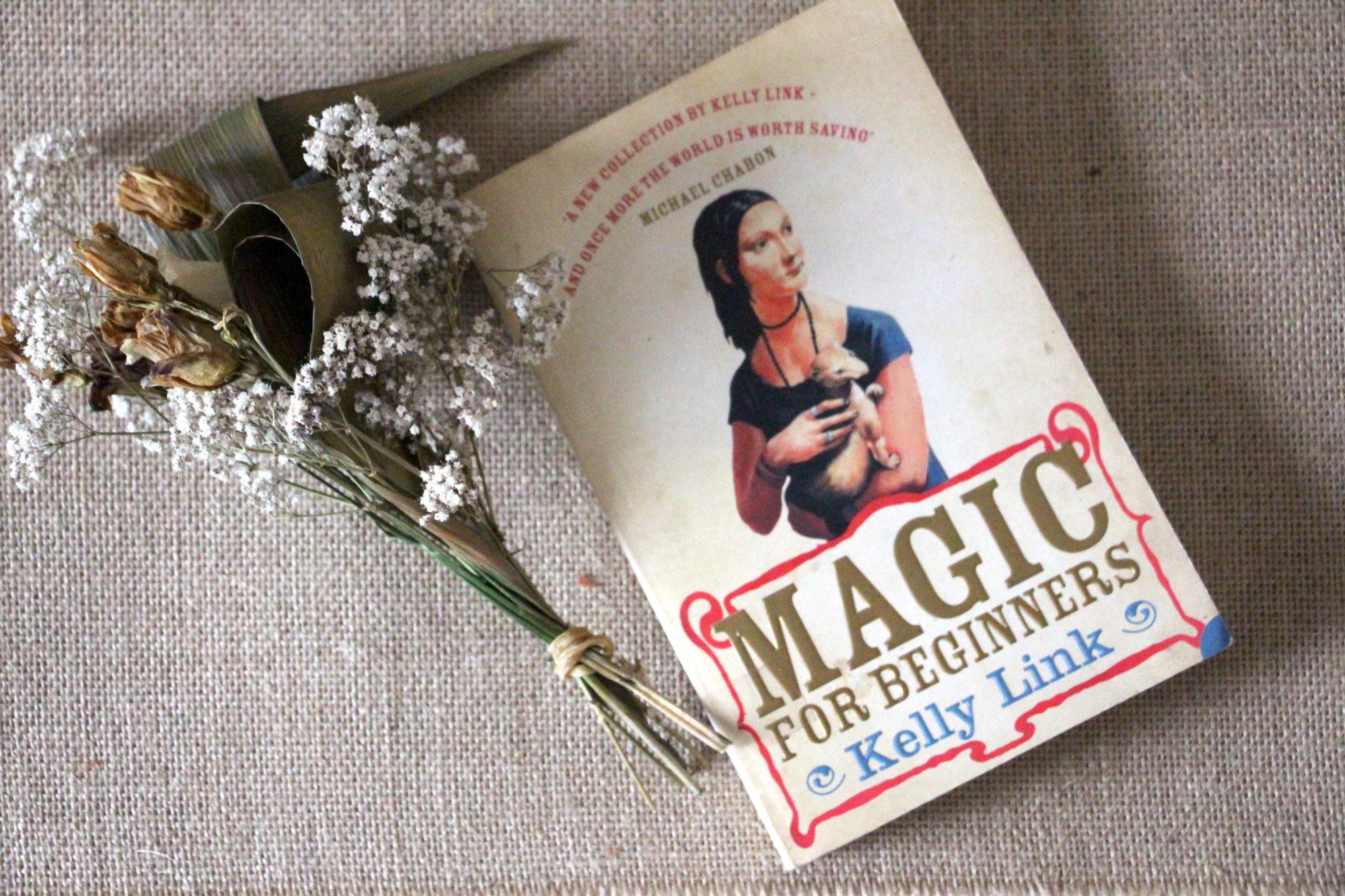

Magic for Beginners is the perfect blend of magic and real, strange and banal; it’s everything I want to do with my own writing, and now I feel, like another good friend told me she did with her favorite childhood book, that I just want to have it with me, always, and carry it around like a good-luck charm.

The nine stories in this book are lyrical and strange, beautiful and open-ended. The characters within them take the strangeness of their world in stride: in “Stone Animals,” a man moves from the City to the Country and finds that his lawn is overrun with rabbits and his family is convinced that different normal items in their home – the coffeepot, the television, his office – are “haunted.” The way in which this affects the family is sinister and strange, and the way in which it is described leaves the reader uncertain as to whether the hauntings are real or not, but this seems to be unimportant, in the end.

Some stories borrow heavily from fairy tale mythology, like “The Faery Handbag” or “Catskin,” which reads like an acid tripping version of Hansel and Gretel – I couldn’t get enough.

“The Hortlak” is one of my favorites – and one of the strangest. Two convenience store clerks living on the edge of an abyss have to deal with zombies coming in and buying strange things. (The zombies reappear in “Some Zombie Contingency Plans,” which I found a very clever way of tying the two stories together.)

Other stories seem to fold over on themselves, like the final one in the collection, “Lull,” which contains a story within a story within a story, all of which mirror one another in ways that belie our logic but make total sense to the world that Kelly Link has created.

My favorite story, though, was the title story. It unites the strangeness that Link crafts so effortlessly with this idea of a story folding in on itself with convincing and heart-wrenching teen characters. Of course, this is where Link’s stories meet mine, and I found myself wondering if I should scrap my whole novel and do something else with my idea entirely.

Of course, I came to my senses, but I think this is what great literature does to us. It challenges our view of things; it makes us want to upend everything and see what’s underneath.

Audrey Niffenegger, author of The Time Traveler’s Wife, calls Link “the literary descendant of Jorge Luis Borges and Franz Kafka,” and I am wont to agree. The only thing to do now, then, is to leave you with two utterly beautiful sentences from the stories and to hope that you check them out yourselves.

“Batu had spent a lot of time reorganizing the candy aisle according to chewiness and meltiness.”

“The children of the living and the dead most often take after their dead parents. Life, like red hair or blue eyes, is a recessive gene.”