Protagonist, main character, hero. However you describe this character, they are, more often than not, the driving force of the story. Whether their conflict is external or internal, as massive as the protection of a country from invaders or as intimate as overcoming heartbreak, the main character’s plight is usually what keeps a reader engrossed in a story. So what happens when the main character barely gives us any glimpses into their story at all?

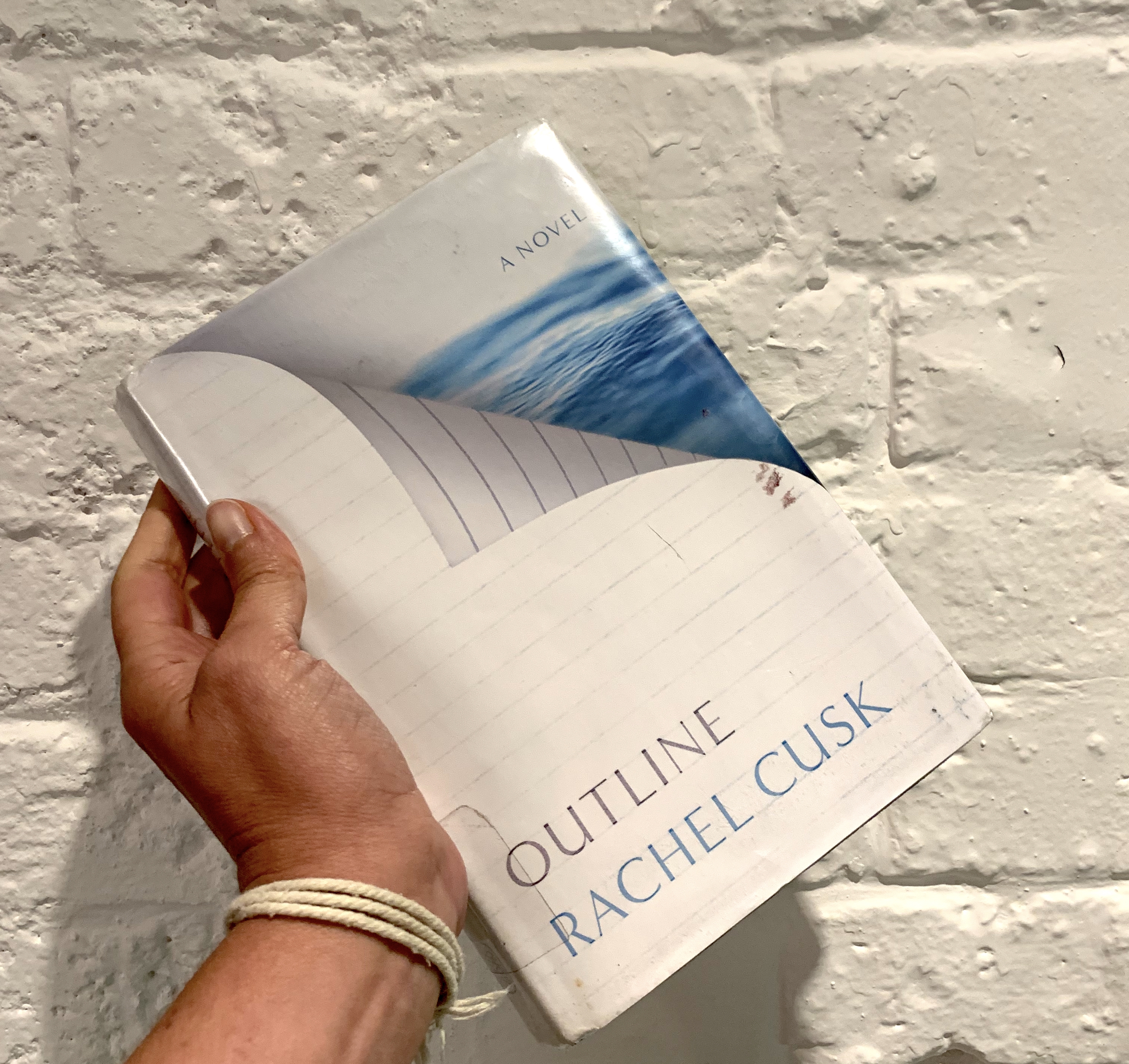

This is the case for Outline, a book by Rachel Cusk that begins a trilogy I plan to devour in the next week. Outline follows a female writer, who we learn more than halfway through the book is named Faye, who is in Greece to teach a writing class. But Faye isn’t really our hero, or even our protagonist. In fact, aside from the fact that she is a writer, a divorcée, and a mother, we know almost nothing about her at all. Her gaze is cool and removed from the world, something she seems aware of as she tells one of her many interlocutors about the ambivalence that plagues her.

These interlocutors are the driving force of the book. Faye encounters many: the man sitting next to her on the flight; a fellow teacher hailing from Ireland; an old friend; her students; a famous female writer; the woman who will be inheriting the borrowed apartment in which she has been staying once she is gone. In verbose, meandering monologues, these characters share their struggles – failed marriages, a hated pet, sexual assault – which are filtered through the ambivalent ears of Faye and thus presented to the reader on the page.

This device should not have worked, for me. I generally gravitate towards a narrator who is, if not more active, at least more engaged in his or her own life. But much like the passivity of many “heroes” in the work of Haruki Murakami, I found Faye, with her guarded inner life and her observant eye, to be a agreeable person with whom to visit the beauty of Greece and the tumult of human existence.