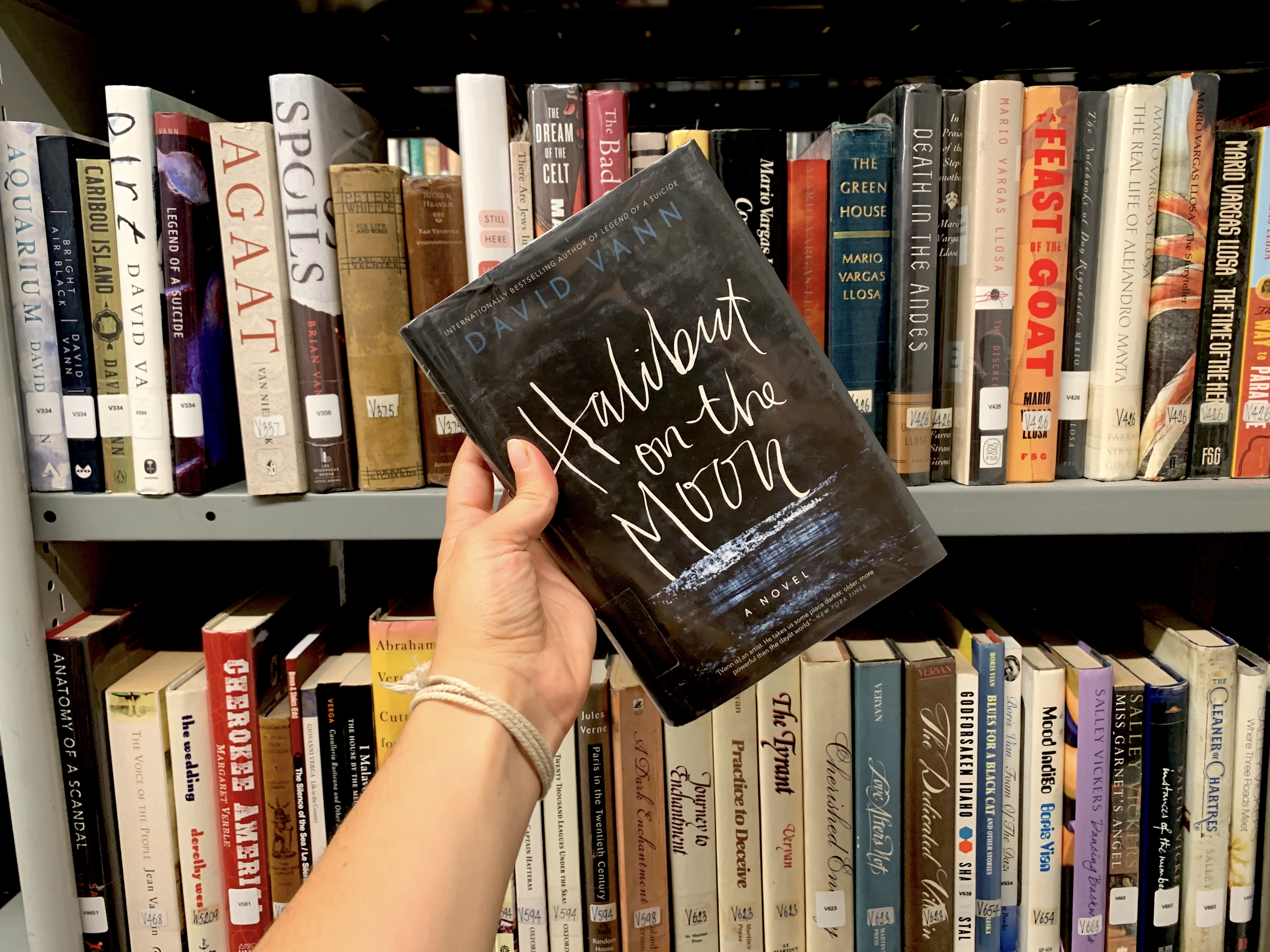

When I first began Halibut on the Moon, it felt like a book about selfishness. I thought it was a book featuring a typical, self-centered, womanizing, white male protagonist, and if not for my rule of never setting down a book I’ve started, I might not have finished it. I did. I realized why I have this rule.

Halibut on the Moon is a book about depression and bipolar that manages to delve deep into the psyche of someone battling these powerful demons. It is the story of a man who refuses to live for anyone else but who feels a constant pain whose torture is the fact that it is so powerful but never becomes acute. Within pages of beginning, the reader understands this man wants to kill himself, intends to kill himself. This struggle – with this inner desire and with the fact that the moment to do so never quite seems to arise, his pain never quite toppling him into the abyss – is at the core of the narrative drama.

For anyone who has been near to anyone with bipolar, the deftness of the description is incredible. I wonder if someone suffering from the disorder would feel the same incredulity before the specificity of the detail and depth with which the author goes into the story, but from experiences being around people with the disorder, I certainly recognized moments, changes in behavior, in speech, in mood.

But perhaps the most haunting part of this book is something I didn’t recognize until the end, though those familiar with David Vann would likely have noticed before. The author’s name is the same as that of the protagonist’s son; this novel is, in reality, a novelization, an imagination, of Vann’s own father’s last days on Earth. It adds a poignancy to the narrative that makes this book even more beautiful – and even more bittersweet.