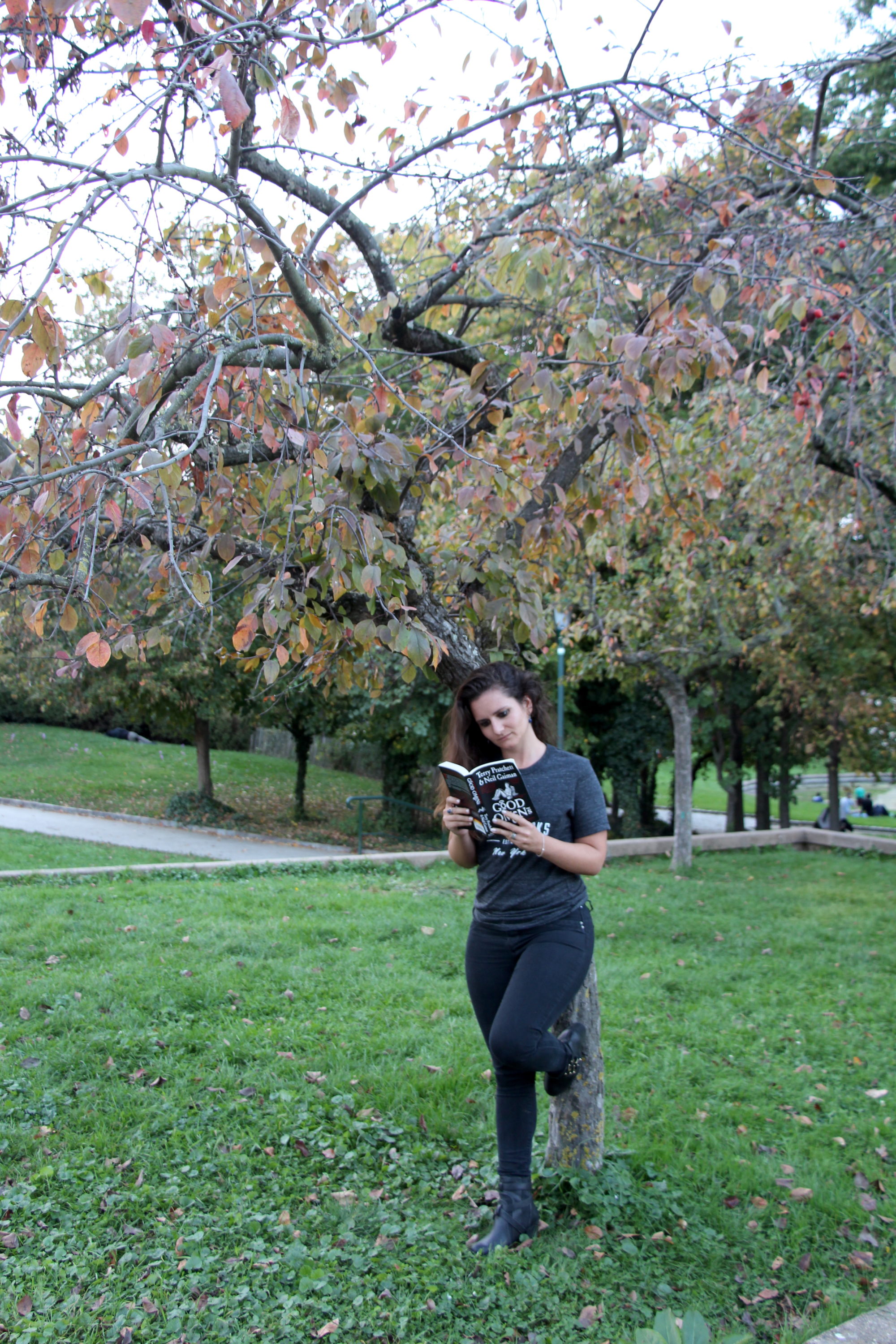

I’ve always been a fan of British humor, whether it’s old-school Frye and Laurie to Doctor Who to the entire canon of Monty Python. And while my forays into this particular brand of wry wit have mostly remained in the world of television, I’ve also loved the entirety of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy for years. There’s something about a writer assuming that the reader is just as intelligent and self-deprecating as he or she is that I enjoy to no end, and that’s exactly what I got when I picked up Good Omens, a collaborative effort from Terry Pratchett and Neil Gaiman.

I had actually recently read another of Gaiman’s works – The Graveyard Book – on the suggestion of a good friend of mine. She had recommended as a particularly good example of a child narrator; Gaiman manages to accomplish this with the perfect blend of astuteness and believability (a feat considering that his main character is a human boy raised by ghosts). I was no less tickled by the character of Adam created by Gaiman and Pratchett together in Good Omens.

This book feels like the sort of work that two friends with a similar sense of humor made up entirely for their own amusement, without ever thinking anyone else would read it. (The interview with the two writers at the end of the copy that I have reinforces this as truth.)

The book charts the eleven years after which the Antichrist is placed on earth as a newborn in a small London suburb; the snake who tempted Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden is one of our protagonists (in this iteration, a Southerner with a vintage Bentley that drives itself and converts any cassette tape left in it for longer than two years into a Queen tape); another is an angel with a particular affinity for the gavotte and antique literature. Elvis makes passing appearances, the true genesis of the M25 ring road around London is explored, and Pestilence is shown to have retired from his place among the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (now the Four Hell’s Angels – literally) to be replaced by Pollution.

Gaiman and Pratchett have a fantastic talent for creating a work that is at once witty and deep, wry yet heartfelt. The very idea of free will is closely examined and then put right back where you found it, and the idea of God’s Great Plan as an incredibly complex game of chess is challenged with the notion that perhaps it’s an even more complex game of Solitaire. And above all, the ideas of the binary of true good and true evil, which have existed only to be challenged again and again throughout history, are tossed out with the rubbish (though the links between traveling salesmen, answering machines, telemarketers, and Hell, are all reinforced).

This fresh take on what it means to be good, what one little boy will do in the face of phenomenal cosmic power, and nature versus nurture is a real trip – I hope you take it. (Especially now that Michael Sheen and David Tennant are slated to star in the film adaptation, much to my neverending joy.)