French university – and pretty much any university aside from American – requires that you specialize pretty early and pretty specifically. If I’d done my undergrad here, I would have had to pick my major before I even picked the school I attended. As it was, I only did my Master’s here, but I still had to know what century I’d be studying – and my thesis topic – before I could begin school.

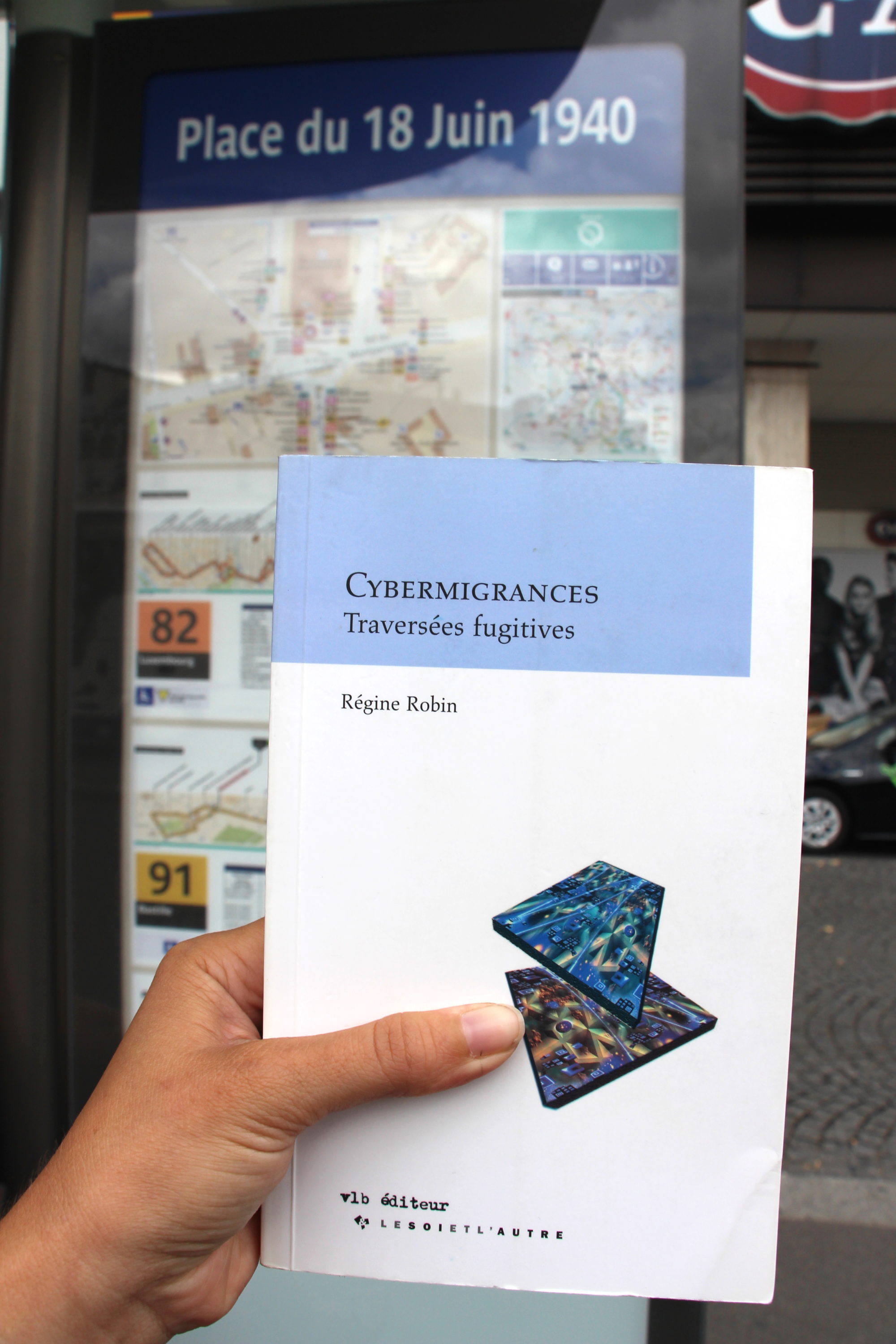

Though I was studying the 19th century, as part of my program, we were also required to take two courses outside of our expertise. The first, for me, was a class on Renaissance poetry which, while it did give me some interesting ideas about the concept of time, kind of went in one ear and out the other. The other, however, was on Francophone literature, and I came out of it with a few favorites, including Cybermigrances. Traversées fugitives by Canadian author Régine Robin.

Robin’s book is a self-portrait in prose. Born in Paris to Polish Jewish parents, an emigrant to Montreal where she is a sociology professor, Robin lives a fractured identity, scattered through multiple places, multiple names, multiple languages. Through its play with genre, form, and place, her series of essays and stories, some fictional, some critical, some surreal, her work reflects this fracture: it is a collage in book form.

Robin splits her time between Montreal and Paris, though the book also delves into other cities, like Berlin. In each, Robin shows herself to be the modern flâneuse, a concept spearheaded by one of my other favorite writers, Charles Baudelaire. A flâneur or flâneuse is a wanderer, a person who communes with a city with no purpose or goal in mind. This is perhaps best exemplified in one of my favorite essays of the book: “L’autobus 91. Montparnasse-Bastille, Paris.”

The essay follows Robin’s experience riding a popular bus line from terminus to terminus, punctuated by individual stops. She explores not only the physical experience of the bus: the summer heat, forgetting her umbrella – to a deeper meaning of each of the stops, from the first, at Montparnasse, where she lives “littéralement dans la gare” – literally in the train station – to the place of her birth, where she takes pictures but feels nothing. She even delves into the history of each place and its importance to the history of France, of the French, of Paris.

This is, in my mind, one of the truest experiences of Paris. One lives, first and foremost, in the real world: there are lines to be waited on, cranky people to interact with, metro tickets to purchase, packages to contain to your knees to leave a seat available for another. There are the links of heart with Paris: the ideals that we create in our own minds, of memories – ours or someone else’s – that Paris evokes for us. And then, of course, there’s its history, the part of Paris that has captivated so many of us from America or Canada or Australia, places where “old” has an entirely different meaning than this city, whose major southern avenues are still based upon Roman roads.

I don’t often ride the 91, but I somewhat fortuitously found myself on it recently, riding nearly the whole line, from Montparnasse to Gare de Lyon. The entire way, I had Robin in my pocket, offering new perspective on the relatively banal experience of public transportation. It made me think of how special riding the bus in Paris used to be, merely because it was Paris; it was nice to be reminded of the person I used to be.