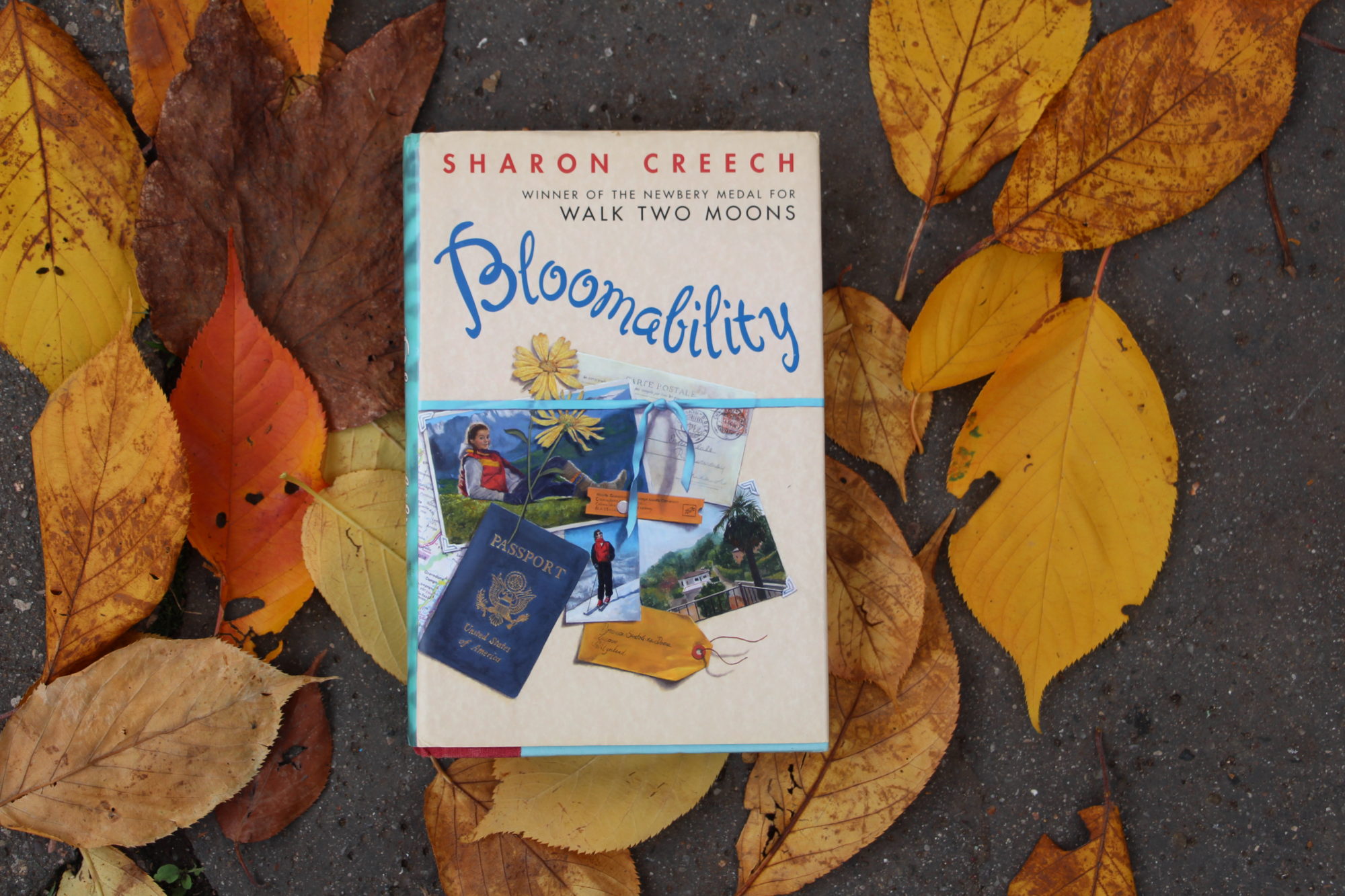

When I was younger, my favorite author of all time was Sharon Creech. I read everything she wrote, from Newberry Medal winner Walk Two Moons to the follow-up Chasing Redbird. And then I stumbled upon Bloomability, which quickly became my first favorite book and – without my really knowing it at the time – would echo and shape my life.

Bloomability tells the story of a young girl living a transient life in the U.S., following her wanderlust-filled father, her city-girl-trapped-in-the-country mother, her pregnant sister, and her troublemaking brother from opportunity to opportunity. While there seems to be no room for Dinnie to bloom into much of anyone, surrounded as she is by all of these strong personalities and endless noise, she is nonetheless horrified to learn that she is being “kidnapped” by her aunt and uncle and taken to Switzerland, where her uncle is running a boarding school: an opportunity that, for once, is just for her.

Eleven-year-old me saw in thirteen-year-old Dinnie everything I had always wanted to be: adventurous and brave, and yes, just a little bit irresistible to the ever-optimistic Guthrie, whose zest for life is constantly opening Dinnie’s eyes to new “bloomabilities” (possibilities), new opportunities, new discoveries. I wanted to spend my winter break skiing in the Alps and eating raclette; I wanted to receive cryptic cards in the mail from my mother and be fawned over by some mysterious aunt and uncle who had no one to worry about but me.

While I didn’t go to Switzerland, like Dinnie did, I did find something romantic in the idea of Europe. I’d never say that Bloomability was the reason I went to France on a three-month exchange program, at fourteen, though I have a hard time now (and had a hard time, then) expressing what actually made me want to go. I remember finding the time between when I applied and when I found out I’d been accepted into the program interminable; I remember my mother asking me, on September 12th, 2001, if I still wanted to go. I remember I took Bloomability with me.

Of course, my experience was nothing like Dinnie’s: I wasn’t in an American school and spoke very little French at the time, so the friendships I made were tenuous at best, held together by strings like the sorrow over the terrorist attacks that had blighted Manhattan the day before my scheduled departure, or the fact that I thought I might know what motocross was (from a Disney Channel original movie, though I did not share this tidbit).

I could fade into the crowd, be pushed along through the tunnel, into the city. I could roll along in my bubble ball.

A year later, I too went to boarding school – in New England rather than in Switzerland. Bloomability came with me there, too, to sit on a six-story Ikea bookshelf while I explored who I was in a far more adolescent way than Dinnie ever did, stretching my identity out on all sides to examine it and see how I thought I looked: punk, grunge, prep, slacker, assiduous, gay, straight. I tested and tried to such an extent that one of my friends called me “lobotomy girl,” in reference to a personality and outward expression that seemed to change every eighteen months, like clockwork.

I was sorry I was so adaptable, and I promised myself that I was going to stop being adaptable. It’s hard to change your character overnight, though.

Bloomability didn’t come with me on my five-week tour around Europe with my high school friends, after I believed I’d decided who I was. But her words echoed as we journeyed around the continent by train, untainted by previous experiences.

All around us people rushed, calling to each other in German and French and Italian. Mostly it sounded like achtenspit flickenspit and ness-pa siss-pah and mumble-mumble-ino giantino mumble-ino.

And now I live in France. I’m more than twice Dinnie’s age (and nearly three times the age I was when I first encountered her), and yet there’s something of Dinnie that still lives on, in me. Bloomability lives in my Paris apartment, now, and Dinnie’s voice informs, perhaps not my decisions, but certainly my writing: Creech manages to capture that divide between the innocence and the oft-ignored depth of a young introvert from a large family who’s still trying to figure out who she is, and for that, both young me and current me will forever be grateful.