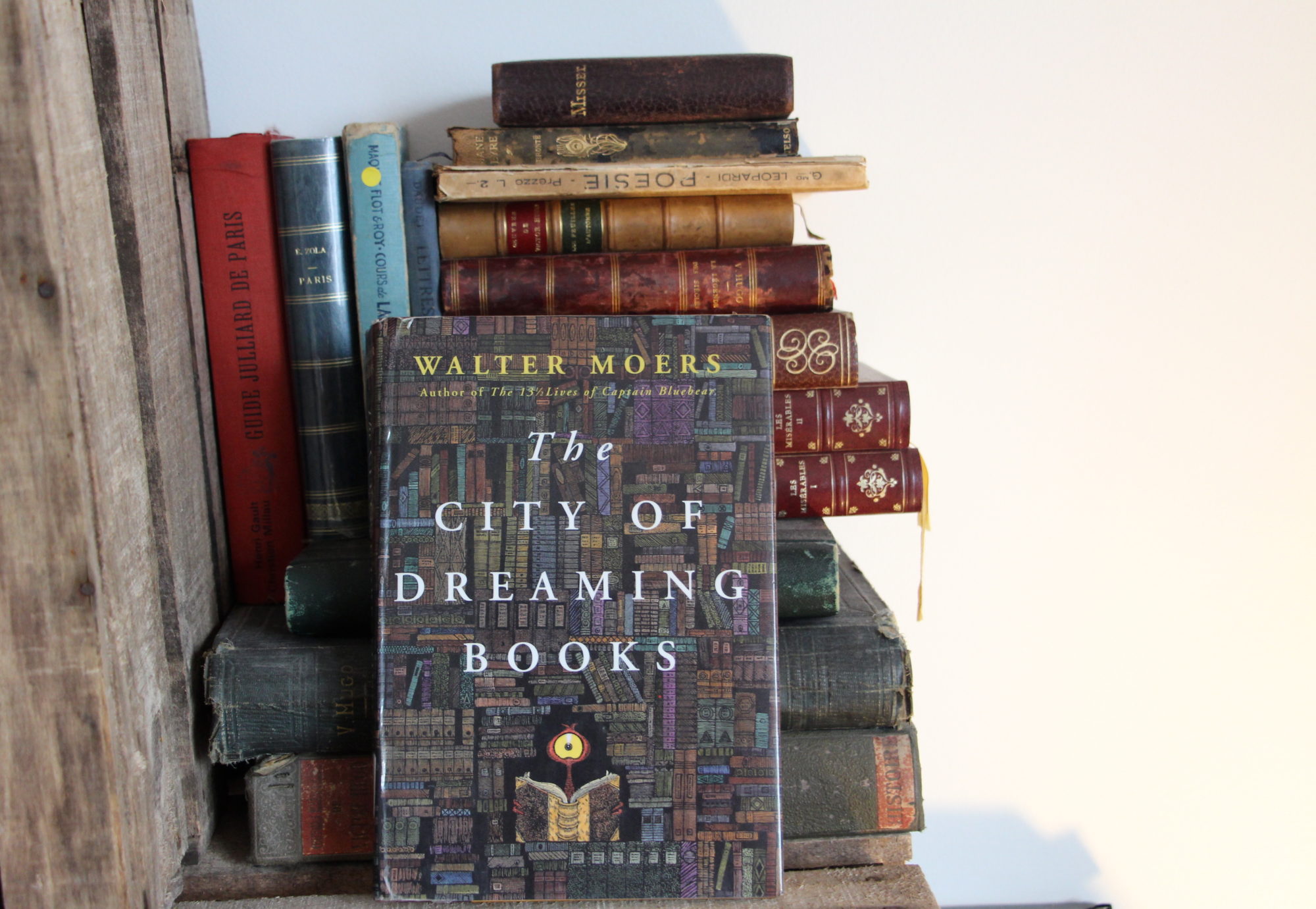

I generally don’t love reading books in translation, so imagine my surprise when I fell head-over-heels in love with this book, translated from the German by John Brownjohn, and from the Zamonian to Walter Moers.

If you’ve never heard of Zamonian, you’re not alone; it’s a language – and a continent – invented entirely by Moers, who purports in this book to be the translator of Optimus Yarnspinner, a dinosaur from Lindworm Castle. The story follows Yarnspinner’s journey from his home to Bookholm, the so-called City of Dreaming Books, to find the author of a manuscript that he believes is the best piece of writing in the world. What for any booklover would seem like a dream come true soon becomes a nightmare, as Yarnspinner is kidnapped and left for dead in the catacombs beneath Bookholm, encountering all manner of horrible creatures beneath the city in his search for the elusive author.

This straight fantasy wouldn’t usually have tempted me, except that it’s about books. I’ll read pretty much anything about books. And while on the surface, the story is a fun sort of jaunt that fulfills most tropes of the fantasy quest, it’s also a very self-aware study of literature and language that any bibliophile will love (a tribute as much to Moers as to Brownjohn, who had no easy feat in front of him.)

Take, for example, the authors that are referenced by Yarnspinner throughout the novel. It took me a while to recognize some of the passages he cites (Shakespeare was the first one I spotted, but then I found some Balzac, too), at which point I realized that nearly all of the authors mentioned are real authors; their names in the book are clever anagrams: Hornac de Bloaze (Honoré de Balzac), Trebor Snurb (Robert Burns) and Selwi Rollcar (Lewis Carroll) all make appearances, as does one of my favorites, Rashid el Clarebeau, better known, perhaps, as Charles Baudelaire.

Just as delightful are the neologisms created in the book, including “rumbumblion” (the sound produced by a volcanic eruption), “nasodiscrepant” (a person whose nostrils are notably different in size), and “glunk” (a sound made with the teeth to indicate satisfaction).

When I read more about Moers, I found that not only is he a fantastically descriptive writer with seemingly boundless imagination, but he was also deemed a persona non grata by the political right in Germany when he published comic strips called “The Little Asshole” and “Adolf.” The author has refused to be photographed ever since.

But more than his colorful prose or the fast-paced story line, the thing that most endeared this book to me was the way in which it manages to use a playful tone and relatively light heart to concoct one of the most meta studies of a piece of literature within a book I’ve ever read. It’s a fantastic study of writer’s block and what leads an author to inspiration, and it approaches these themes in a way that is both self-aware and not obtrusive to the plot.

To say any more would spoil the ending (and I’m sorry to leave you like this, because one of the best characters in the book even notes that cliffhangers are a technique only used by second-rate writers), but you’ll have to pick up a copy to see exactly what I mean.