If you’ve hung around me at all in the past five or so years, I’ve probably talked to you (whether you wanted me to or not) about the Enneagram. A nine-point polygon of personality types, the Enneagram doesn’t seek to tell you who you are but rather to help you get in touch with your core motivations: what you fear, what you crave, how you react when provoked. It’s very complex and very interesting, and I highly recommend you seek out someone far better than me to explain it to you (like Russ Hudson), but I digress.

For simplicity’s sake, let me say this: In the Enneagram, each point on the polygon is assigned a number. It’s not a ranking, it’s just an identifier. And I’ve never read work by someone so clearly a type 8 as Rachel Cusk’s. (I assume that such categorization would appall her, as 8s tend to hate being hemmed in.)

If you’re not a fan of the Ennagram, let me explain it this way: imagine a woman, an artist, who has crafted her perfect Eden of safety – a space and a place that she can inhabit without fear of being intruded upon or controlled. She can write there. She can explore nature there. And then she invites a writer she looks up to to occupy her space (aka, a wholly separate house on the same property – let’s not get crazy, here; she is an 8 after all), only to find that he perceives her with disdain and mockery. He refuses to see her. He refuses to acknowledge her in the way she feels she deserves to be acknowledge.

You can only imagine what sort of internal mayhem and toil ensues.

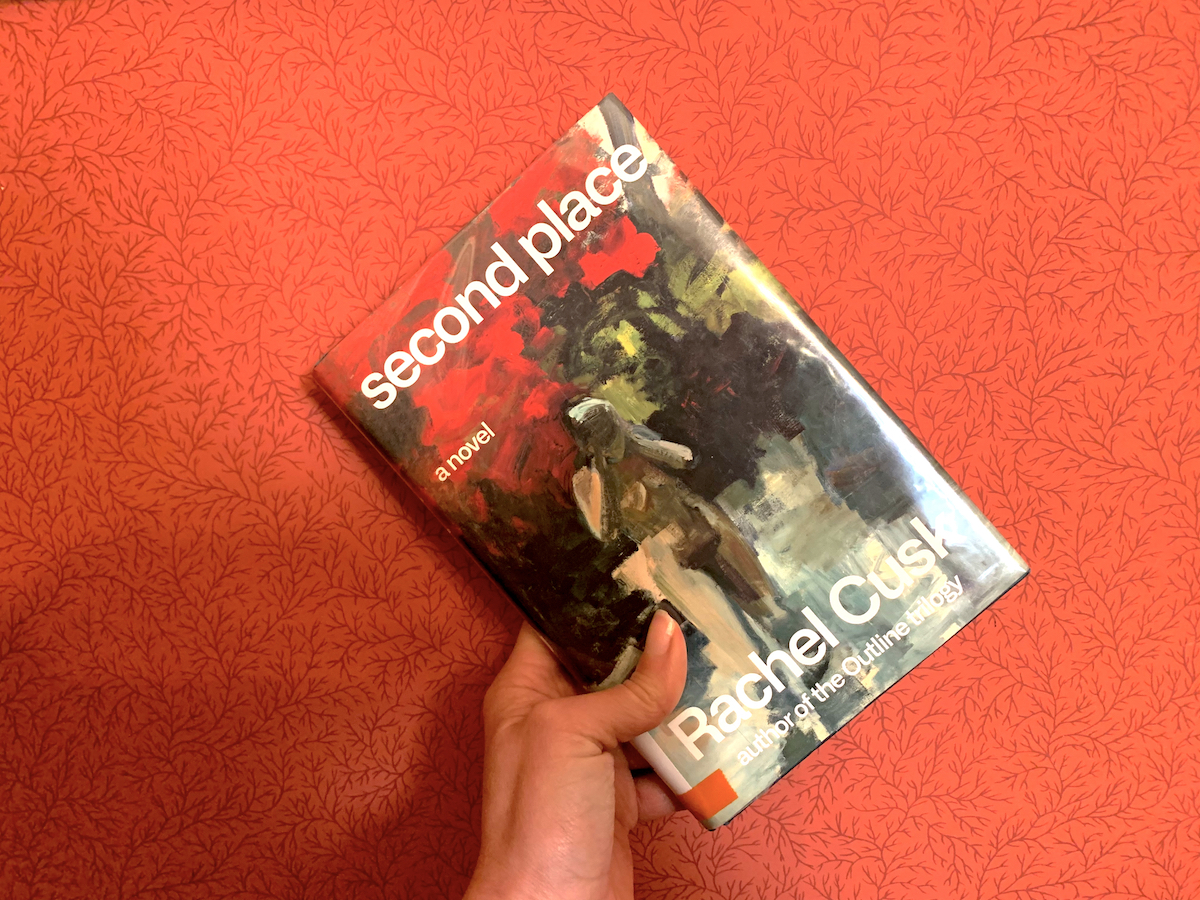

Second Place is the second novel I’ve read by Cusk, after falling in love with Outline, the first in a trilogy I somehow never finished (likely because I ended up at the bottom of my library waiting list for volume two). The literary style of her prose is impeccable; it’s pure joy to read. But more than just the poetry of her words, this book offers a sort of looming, parasitic vibe coming, not from any outside influence, against which the protagonist has skillfully and diligently protected herself, but from within her own mind. It’s got touches of contemporary horror baked into it, albeit less as a fully fledged genre than as a wink, a nod, something perceived just barely, out of the corner of your eye. It’s a theme that’s only highlighted by allusions to the zeitgeist: Covid, lockdown, the persistent need – for women, for women writers, yes, but for all of us, too – for a room, a space, of one’s own. A place where we can feel safe. A private place that, when opened to others, runs the risk of being tainted.

Almost immediately after finishing this book, I listened to this Hay Festival interview of Cusk, which, despite the unfortunate choice of moderator (lots of hemming and hawing, which was only magnified in juxtaposition with Cusk’s cool, calm, collected, confident demeanor) opened my eyes to even more elements of the book, including but not limited to what it is to be a female writer today and when is the right time to name a novel.

Read the book. Listen to the talk. I’ll be over here, busy digging up everything else Cusk has ever written.