What if our identities were not objective, but subjective? What if we wielded our own brush or pen; what if we were active creators of our pasts?

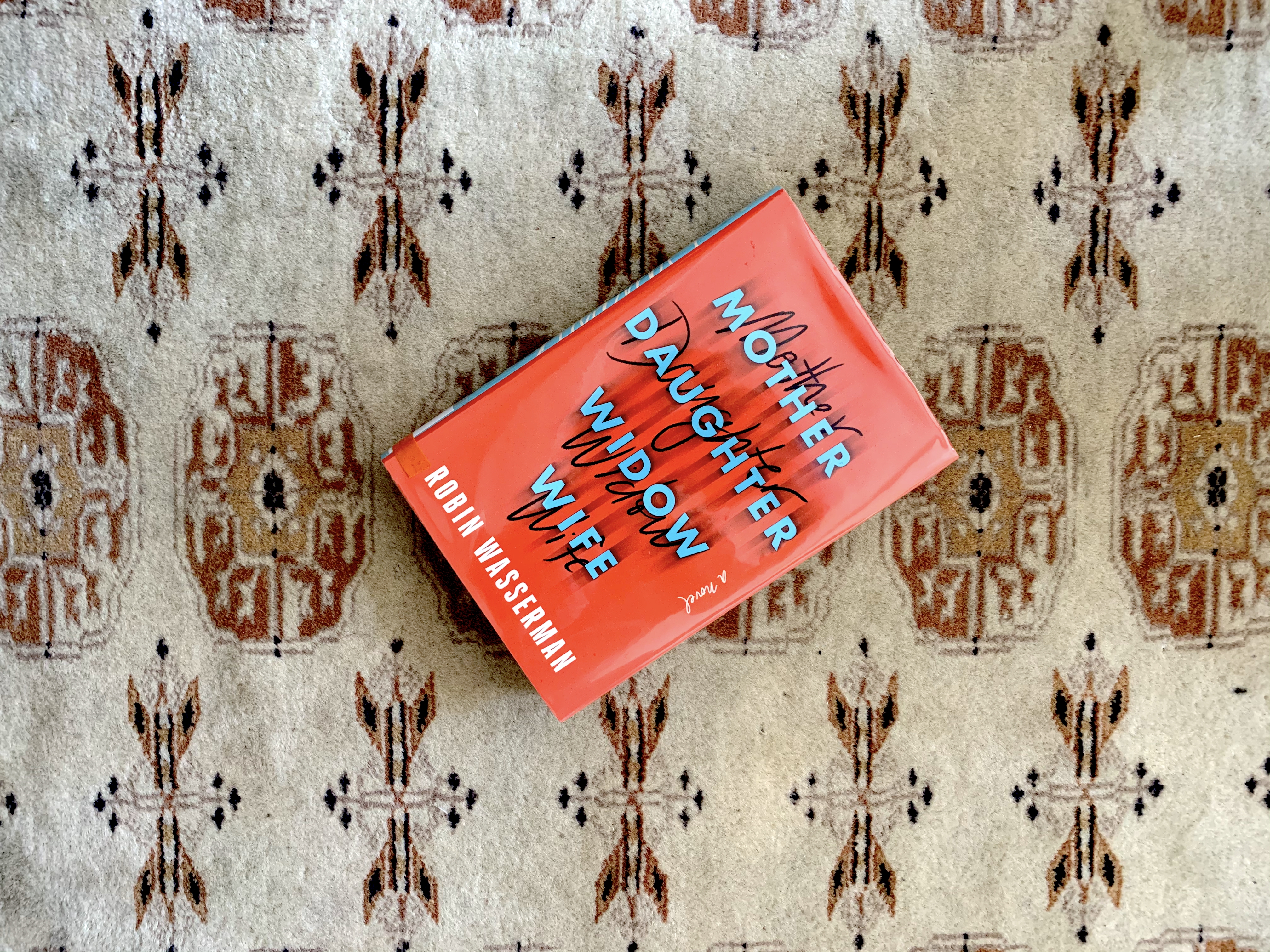

This is the thesis that Robin Wasserman posits in the multi-POV Mother, Daughter, Widow, Wife, which explores the effects of the sudden appearance of a young woman in a fugue state on a young postgrad fellow, her male supervisor, and the fugue-woman’s daughter, over time. The novel, told only from the points of view of the women in the story, explores the ways in which we can control our own narratives, essentially rewriting our memories through time. With themes as far-reaching as wandering womb hysteria, sexual assault, and the Holocaust, it somehow still manages to be an enjoyable read whose story is driven forward by the central protagonist, alternately referred to as Lizzie and Elizabeth.

This book wants to do a lot, and in many ways, it succeeds. Wasserman’s scientific background lends credence to much of the nitty gritty pertaining to afflictions of the memory, including short-term memory loss and a disorder where one creates new memories that are not one’s own. But I have a few bones to pick, most of which relate to the fact that I think this book tries to do too much and comes up short. One of the key whys through the book is never answered; the focal point instead seems to shift in the latter third of the book, leading to a denouement that ultimately, unfortunately, falls flat.

I loved many of the themes here, including the ways in which who is telling a story (on the page or in life) naturally changes the story itself. I very much enjoyed the exploration of keeping secrets from oneself. And I loved many of the quirks of characters: a journal of first memories, for example, or the recurring musical fugue answering the mental one. But perhaps the biggest hindrance to my truly enjoying this book was my inability to connect with one of the main protagonists.