If you spend as much time on YA writing Twitter as I do (yes, that’s a place, and it’s awesome), you’ll be well acquainted with #OwnVoices, a hashtag – and concept – that is rightfully gaining traction in the writing and publishing spheres in the YA world and beyond. The idea behind #OwnVoices is that stories about marginalized people should be written by people from those marginalized communities, and this for a number of reasons.

Number 1: it’s important to make sure that writers from privileged groups aren’t profiting from the rise in interest in the experiences of the marginalized. For years, these groups were not given any way to gain access to the publishing sphere, and the increase in interest in their stories should pave the way for greater access.

Number 2: The best way to authentically tell the story of someone from a marginalized group is to ACTUALLY ASK A PERSON FROM THAT MARGINALIZED GROUP.

(Apparently I have strong feelings about this.)

But seriously, for years decades centuries in media, the experiences of marginalized characters – and specifically black characters – were used as a way to paint the background of a story for the “main” (read: white) character. Black characters were reduced to a trope (The Sassy Black Friend; the Magical Negro; the Benefactors of the White Savior), and the lived experiences of Black people were overlooked in favor of this broad-brushstroke version that was deemed palatable to white audiences. A move towards marginalized people – and specifically Black people – telling their own stories was long overdue.

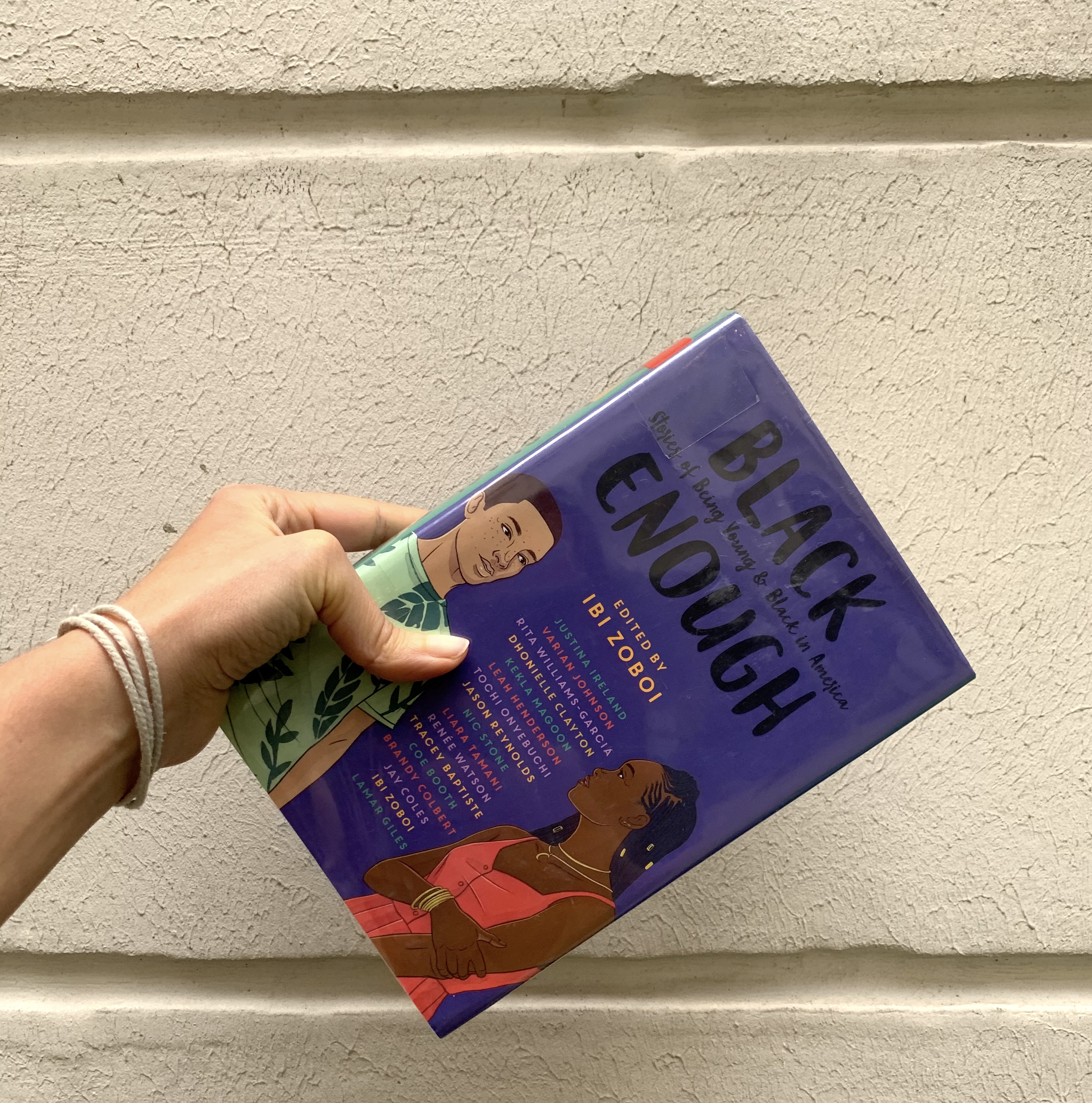

Which brings me to Black Enough.

This anthology of short stories unites a panoply of experiences of Black teens, all written by Black authors. Some look at Blackness head-on, as in one story exploring a teen who visits her grandmother and cousins who live in a predominantly black community. Some are intersectional, blending experiences of Blackness with, for example, experiences of queerness. And some are stories about existing while Black, as in a story about a Black teen participating in a Hack-a-thon, or one about a group of Black friends deciding what they’d most like as an after school snack, or one about two half-sisters finally reconnecting at a summer camp.

The quality of the stories, as I’ve found previously in multi-author anthologies, varies widely. Some stories are astute and resonant and poignant; others seem to be attempting to use a sledgehammer to kill a fly in their approach to the thesis statement suggested by the title of the book: “All Black people are Black enough.” The pleasure of this anthology is not in finding one, singular response, but rather in encountering the myriad approaches to individual responses from each of the authors, delving deeply into experiences that have not yet enjoyed the attention of such a wide variety of readers.