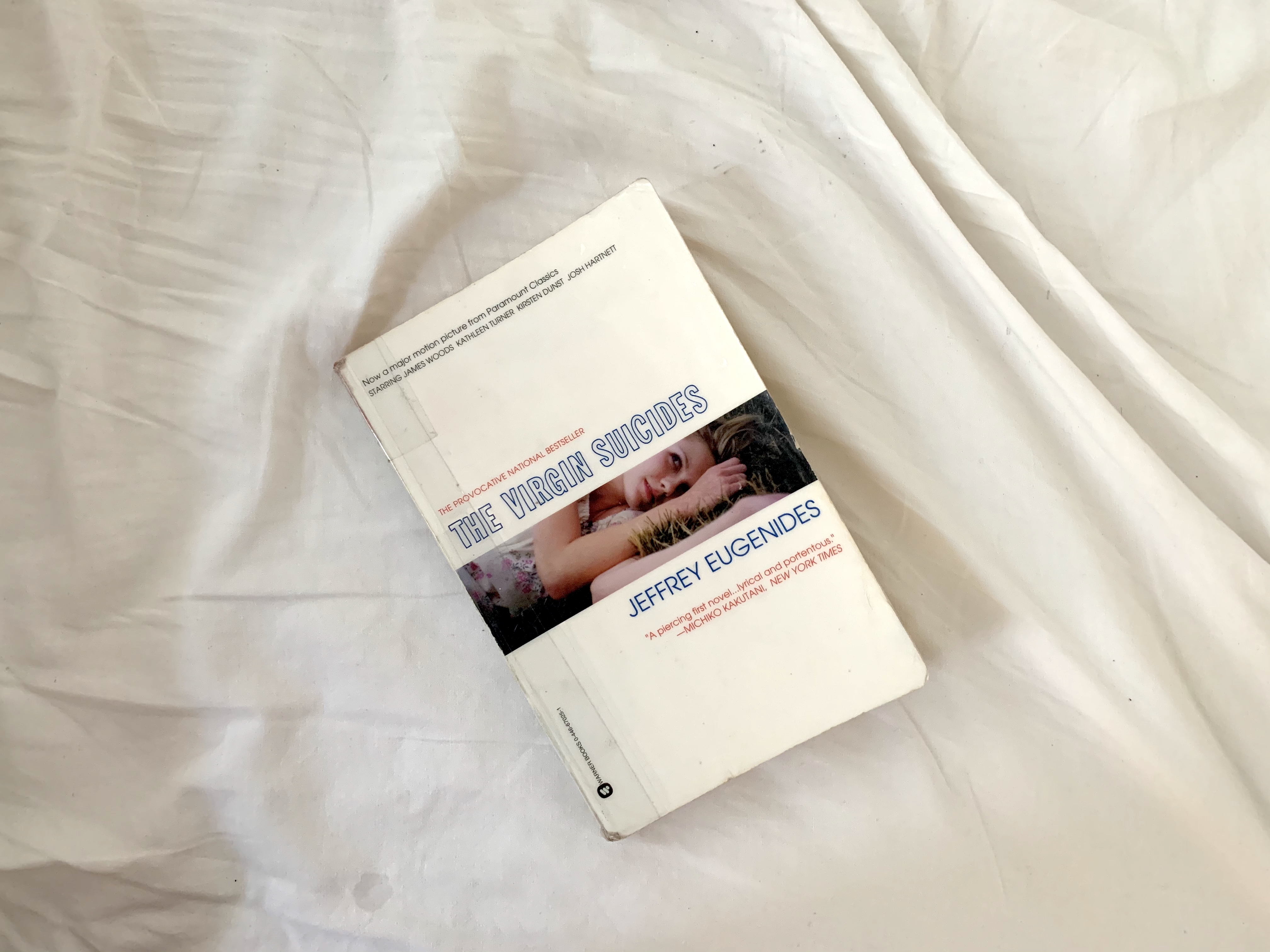

As I’m sure most of you know, I went to a boarding high school when I was a teenager. I didn’t watch much TV while I was there – we didn’t really have the time – but every once in a while on a Sunday afternoon, I would go downstairs, and we would put on one of a selection of movies we had on VHS. School Days was a popular one; so was Crazy/Beautiful. And apparently, there was some major Kirsten Dunst fangirling going on, because we also watched The Virgin Suicides quite a bit.

It wasn’t until recently that I realized that while I had seen the movie at least a dozen times – and I was sure I’d read the book – I couldn’t for the life of me tell you what it was about. And so I reread it. And much like rereading The Great Gatsby years later… I found that I was much mistaken in my first impressions of it.

The Virgin Suicides, as its title suggests, is about a series of five suicides that plague a small town, all occurring within a bit more than a year, all occurring within the same family. What struck me the most upon rereading The Virgin Suicides all these years later is the point of view chosen by Jeffrey Eugenides. The story is told from the perspective of a “we,” a group of boys watching the five Lisbon girls grow up across the road. From the very beginning of the book, if the title didn’t give it away already, the reader knows that all five sisters committed suicide. The narrator and his peers, now middle aged and living their own lives, have assembled a sort of collection of evidence to figure out the reasons behind the suicides. But this device is merely a lens: we never really see our modern narrators (and we never really meet our narrator, who unlike his peers, is never mentioned by name, at all).

The story is ostensibly about the Lisbon girls, but in reality, it’s about the boys’ gaze, their obsession. Despite their stated mission, the boys never get to the bottom of their question of why… and as a reader in my 30s, I think I can answer it for them: they didn’t want to know.

The girls were not girls, but a construct of what the narrators wanted them to be. Even the tagline for the movie, made by Sofia Coppola, of all people, notes that “It didn’t matter that they were girls. It only mattered that we loved them.” As a reader now, I wonder how a teenage me never quite grasped the fact that it did matter; of course it mattered. And the fact that it mattered to no one is part and parcel with why they died in the first place.

This book is an enthralling look at the power of narrative stance to change, not just how one tells a story, but the very story one is telling. It’s a story that keeps the reader at an arm’s length the entire time, and yet one can’t help but devour the whole thing.