I don’t take much vacation. If you look at my Instagram account, you may be tempted to call me a liar, but let me be clear: I travel a lot. I’m just always working, too. Even if it’s just a few sneaky hours before anyone else has gotten up – or after folks have long since gone to bed – I’m a pro at hiding out in the bathroom, on the balcony, or even, on one recent occasion in Shelter Island, in the parked car to ensure that I can continue to maintain the lifestyle to which I’ve become accustomed.

The closest I ever get to a vacation is, of course, the five days I spend in Cannes every summer with my friend Scotty, as we have every year for the past… five? Six? We’re never quite sure. At this point, our time in Cannes is down to a science: our picnics are assembled of bits and bobs from Monoprix and feed us for both lunch and dinner. We ride the ferris wheel. We watch the fireworks. We eat tarragon oysters at Astoux.

And of course we read. A lot.

Our days are spent stretched out on our favorite bit of public beach between Cannes and La Bocca, where we plow through piles of novels, only interrupting ourselves periodically to ask, “Sea?” And while I always promise myself I’ll read “serious” books, the truth is that while Scotty is always diligently reading a history book or a classic novel, I’m usually zooming through the latest dystopian YA.

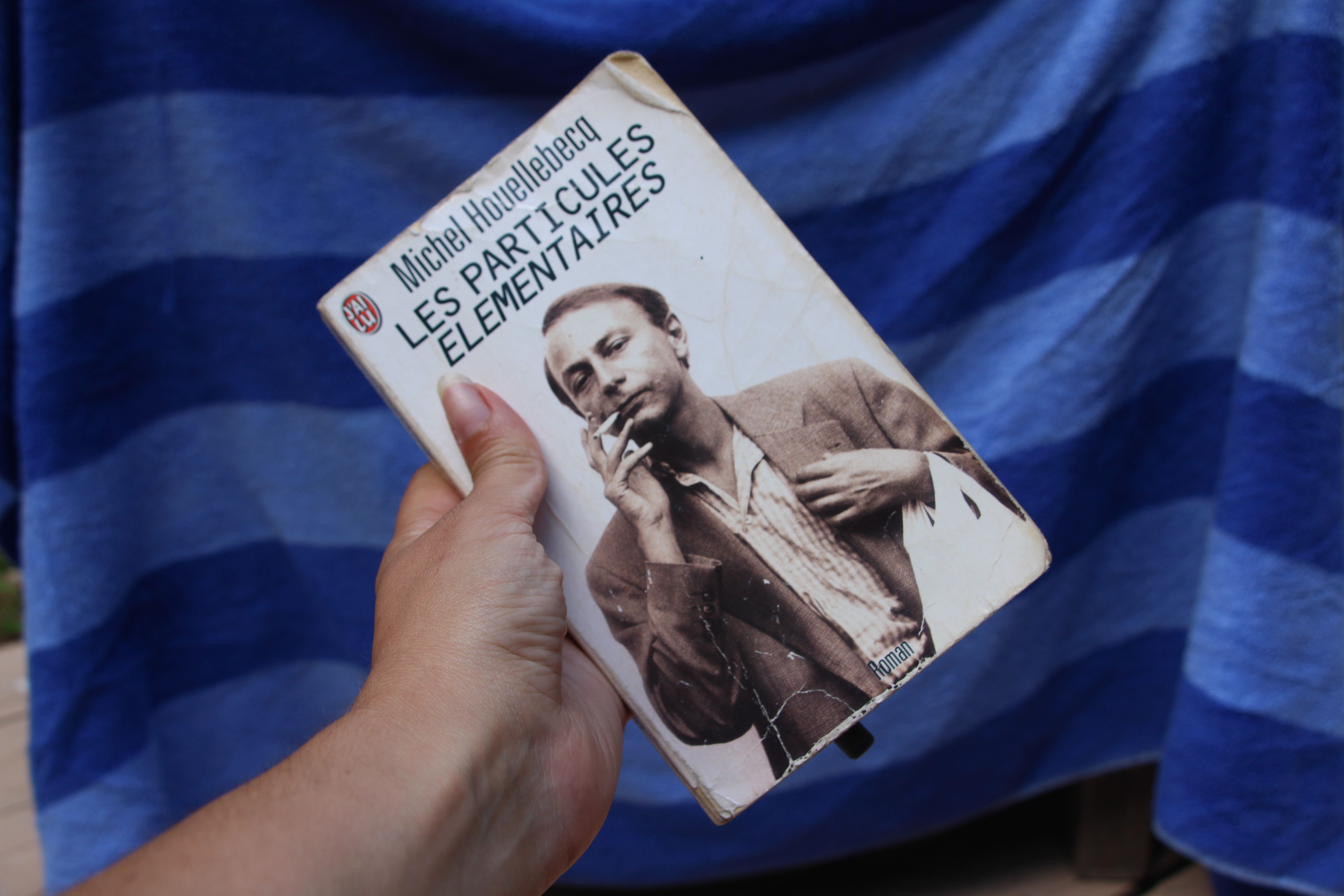

For the past four years, I’ve been pretending to myself I’ll finish Elements particulaires, by Michel Houellebecq, reading 20, 30, 40 pages and then abandoning it for a whole year, which means I have to start all over again by the time the battered paperback makes it back to Cannes again.

But this year, I finally did it.

I’ve been known to flippantly put most modern French novels into one of two categories: sad, wayward, middle-aged woman gets pregnant just in time to see her mother die and is still sad and wayward at the end; sad, wayward, middle-aged man has sex with young ingenue to feel more like a man and is still sad and wayward at the end. This book seemed like it was going to fall into the latter category, with much of the action happening in the past for the better first half of the book and two wayward protagonists rather than one.

And then things changed.

I shouldn’t have been surprised, really. Houellebecq is a known reactionary and even had to flee France to Ireland following a racist controversy, but he’s also lauded as one of France’s greatest living writers.

But let’s begin at the beginning, for the book does have a plot that’s slightly more complex than the one I’ve detailed above. It charts the lives of two half-brothers from the 60s through the early 2000s, detailing the ways in which these two wholly different people brush up against love. Anger, passion, sexual frustration, loneliness, and withdrawal all surface as the two men circle one another, leading to a wholly surprising yet (mostly) well-earned conclusion.

I’ll admit, the story wasn’t what gripped me, not until the last ten pages, which I devoured and could barely believe I was reading. No, what I enjoyed most was what, it turns out, most love about Houellebecq: his sensationalism. Houellebecq knows how to shock, to create characters so abhorrent and cruel and yet so believable it’s sometimes hard to dissociate the characters from the man, to not cast aside the book in anger, thinking that the diatribes you’re reading are the beliefs of the author himself.

And yet, there were a few gems scattered throughout this novel that I found most pleasing, like the musing that seeing as humans today go through at least one crisis over the course of their lives, it is “normal” for them to have access to an establishment open all night in any European capital. The idea that a city would be obligated in some way to subsidize its citizens’ existential crises with 24-hour access to coffee and kirsch is just… the Frenchest thing I ever did hear.

I also loved the idea that depression often manifests by people losing interest in things that “are, effectively, of little interest.”

“This is why one could, in a pinch, imagine a depressed person in love, but a depressed patriot seems frankly inconceivable.”

And then, of course, there’s the criticism of Anglo-Saxon dark humor. Houellebecq writes that while in some cases, one can see the humor in everything “practically up to the end,” “definitively, life breaks your heart.”

These gems kept me reading when I got a bit lost in the toxic male gaze, in over-wrought scientific details, in over-wrought sexuality (though one particularly keen juxtaposition of bouillabaisse and an orgy was, for lack of a better word, genius). While I believed at some stages – because of the sensationalism surrounding Houellebecq, because of the characters who seemed so very devoid of pathos – that I was reading a book devoid of moral compass, the revelation towards the end that fraternity was “the most necessary element to the reconstruction of a reconciled humanity” proved that Houellebecq had pulled the wool over my eyes – and the conclusion of the plot did so even more.

I can’t speak to any translations of this book, but I look forward to being surprised, shocked, horrified, and moved by Houellebecq again.