Writing has, without a doubt, changed the way that I read.

I’ve always read; I still remember the very first book I read (a blocky book with cutout hearts that overlaid one on top of the other on top of the other. I read it to my great-grandfather, and he was quite impressed.) For someone who, for a very long time, couldn’t see much of what was going on around me (I’ve worn glasses since I was four but didn’t actually get the right prescription until I was ten), books were my solace, my escape, my home.

But I’ve also been writing for a very long time, at least since I was nine. It wasn’t until I finally managed my dream – writing as a career – that it changed the way that I read.

Now, whenever I read a book, I’m editing, at least a little bit, in my head. This feels repetitive. This isn’t starting in the right place. This dialogue feels stilted. (Most of the time, it must be said, the things that I edit in my head are things that I’m concerned about in my own book rather than true criticisms of the one that I’m reading.)

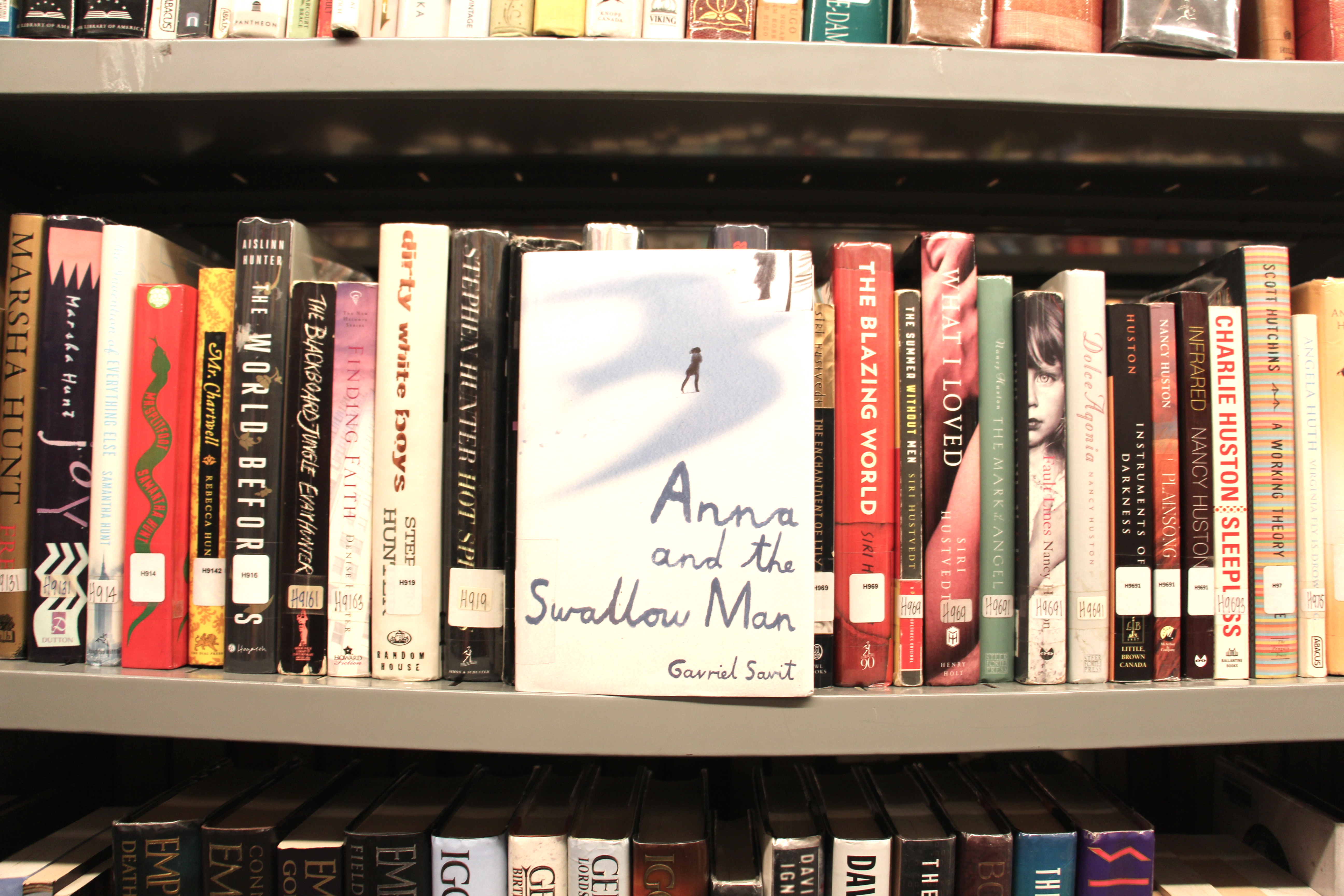

But it’s also changed the way I read in another – far more upsetting – way: sometimes, I have to reconcile my enjoyment of a book with the fact that I’m jealous of just how good it is… And that’s how I felt when reading Anna and the Swallow Man.

This book, set during World War II, completely overhauls the World War II genre, the young adult genre, and even the child protagonist genre. It’s new; it’s exciting. I love it so much it makes me simultaneously want to read it all over again and never read it again.

The story follows Anna, seven-years-old at the beginning of the book, who is left behind after her father is taken to a concentration camp. Left for dead by a friend of her father’s she was sure would help her, Anna is taken under the proverbial wing of a man known only as the Swallow Man, who guides her through rural Poland (and briefly, one of the nations over the border that would later become part of the Soviet Union) over the next few years. The book has elements of magical realism and is highly literary, something I absolutely love in YA literature.

I think my favorite thing about the book isn’t the story or the setting, though both are tantalizing and delicious, but rather the protagonist, Anna, who is, as she constantly reminds us, precocious. At seven, Anna is already fluent in a number of languages, thanks to a linguist father who speaks to her in Polish, Russian, Yiddish, French, and German, among others. Not only an excellent tool for navigating the xenophobic late 30s in Poland, the skill allows Anna to keep her life – and is the quirk that introduces her to the mysterious Swallow Man, who adds “bird” and “Road” to this already long list of languages.

One thing I particularly loved about the book’s use of language was how it allowed Anna to understand notions of different realities: like a truly bilingual child, Anna is comfortable with the synonyms, with the idea that just because you refer to something in different ways doesn’t change the essence of what it is. It is, in fact, with this idea that the Swallow Man manipulates young Anna into lying, ostensibly to keep them safe as they trek through the wilderness.

While reading this book was a beautiful journey, I do have to say that there were moments of the ending that I found disappointing, including a questionable scene of sexual assault and an epilogue that answered none of the questions that had been posed in the twenty pages preceding it. Author Gavriel Savit has mentioned in interviews that his goal in writing the book was to ask more questions than he planned to answer; he has certainly made good on his promise.

Despite these slight hiccoughs, this book is an excellent example of how young adult literature is growing and changing; this book is appropriate for older YA readers, but it’s also an excellent choice for adult readers seeking a believable, if precocious, child narrator and, above all, a literary work with lots of different elements to explore.