I went through a period, in high school, where I felt like I needed to read all the classics.

My definition of “classic” was rather loose: it ranged from Dickens and Shakespeare through to Salinger and Hemingway and Bukowski. (And yes, I know that this list is entirely made up of white men. It took me a really long time to not want to be a white man, because then I’d be able to be a “writer” and not a “female writer.” Self-hatred stemming from cultural expectations: it’s real.)

I don’t think I was conscious of it, at the time, but I know now that the reason I wanted to read all of these classics was because reading something that large swaths of other people have already read and determined to be “good” takes the guesswork out of it. In choosing pre-ordained “good” books, I didn’t have to decide whether or not to like them: I would like them because they were good, and if I didn’t like them, it wasn’t a reflection on the book so much as it was a reflection on me.

Reading: standing in for psychoanalysis since 1992.

All this to say, I eventually evolved past this type of reading. For a while, my sister and I would do the exact opposite: biking to our local library and checking out piles of books based solely on the cover art – or even reaching out blindly and pulling a tome off the shelf. I read some great books that way; I also read some terrible ones. And I read some books that other people would probably love that I did not – and that’s OK.

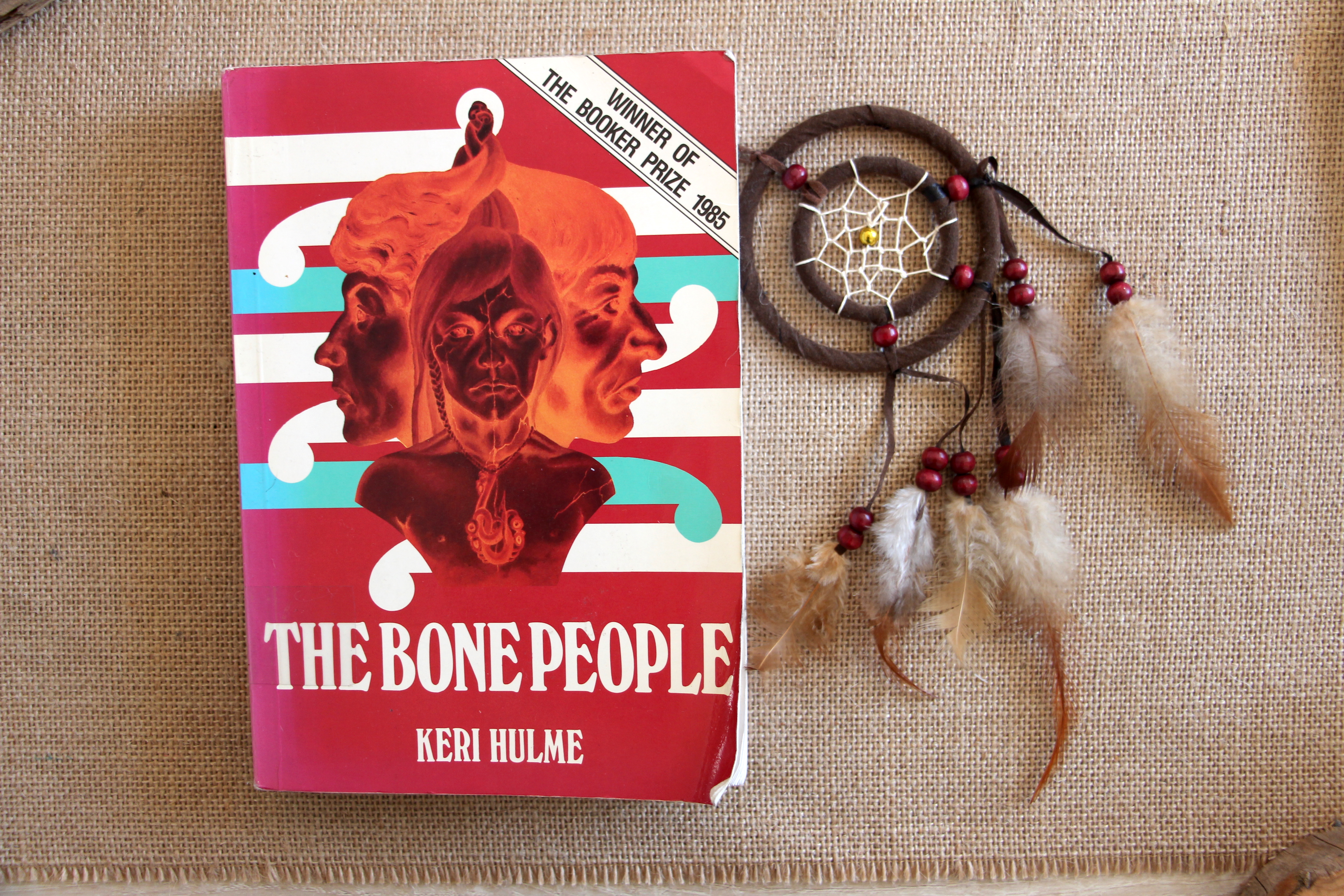

I’ve been checking The Bone People out of the library for months, and for some reason, I always pick another book in my stack to try. There was nothing about The Bone People that repelled me – it just never grabbed my attention as much as others. When I finally cracked the spine last week, however, I regretted having waited so long to discover it: this book is one of the meatiest, most nourishing, interesting, captivating books I’ve read in longer than I can remember.

The book tells the story of three people who meet under rather unique circumstances in New Zealand. It’s a story of regrets, of found families, and of the power of love. It’s a story of journeys, of big mistakes, and of the meaning of home.

But like with so many of my recent favorites, it’s not necessarily the story that’s told, but how it’s told, that so captivated me.

The book deliberately keep the narrator at a distance, intertwining dream and reality, first, second, and third person, English and Maori, thought and action. It’s not the sort of book you can read quickly – it took me ages to get through, and not for lack of trying. I committed myself to this book, but I would only be able to get through 10 or 20 pages at a time; it demands reflection, rereading, lingering. It changed the way I usually read, and for the better.

It also won the Man Booker in 1985, and the moment I finished it, high off of that feeling that surfaces when you finish a truly excellent book, I immediately delved into the list of Man Booker winners from previous years, and my old M.O. of reading only “the classics” came back to me in a rush: was I doing the same thing, now, by scouring the Man Booker list, resolving to check them out of the library as quickly as I could devour them?

Maybe – but it feels different now. I know what I like, and I know what I don’t like. Just because a book is critically acclaimed doesn’t mean I’ll like it (I can think of a handful I’ve read recently that I positively despised). Maybe my approach is healthier now; maybe I’ll find Man Booker winners I don’t like. But this book I love, in the way you love something you barely understand but want so badly to. If you read this book, you’ll understand just how appropriate the sentiment is.