I’m generally not a huge fan of bestsellers, and that’s not because, as my sister and father have both noticed, I “like being difficult.” (Though that is also probably true.) The reason I tend to shy away from commercially popular books is the same reason that after taking too many cinema courses in college, I stopped enjoying movies for a while: I spend too much time thinking about story.

Now, before I get people’s panties in a twist, allow me to explain. I’m working on a novel (and have been for pretty much as long as I can remember [though it’s not always the same novel]). Most of my friends here in Paris are also working on novels, and whenever we get together, we spend our time workshopping one another’s work, talking craft, sharing our opinions on the latest craft essays, and suggesting craft books to one another. I spend an inordinate portion of every day reading and thinking and talking about storytelling, plot points, creating tension, dénouement, dialogue tags, and word count. And I spend a lot of time worrying about the way that you’re “supposed to” approach all of these things.

Because whether we notice it or not, Hollywood blockbusters and bestselling novels have something in common: they’re formulaic. I’m not saying the stories are (although this is often – not always – the case), but there’s a rhythm to a bestselling novel that, when you know the signs, you can get used to. When I was taking cinema classes in school, I remember getting to a point where I would instinctively glance at the clock at minute 20, because that, generally speaking, is when the first conflict arises for the main character. And it kind of took me out of the movie-enjoying experience. Now that I’m spending so much time analyzing what makes prose work, I find the same thing to be true of a lot of commercial fiction. Within a few pages, I feel like I know what the story is attempting to do to me, and so I have a harder time getting lost in it.

This isn’t to say that it’s bad; far from it. It’s kind of like when you write a sonnet: you have a formula, and you have to make your ideas fit into the formula. It requires an enormous amount of artistry, and the resulting poem is beautiful… but when you spend all of your time thinking about sonnets and banging your head on your desk because you can’t figure out how to make your idea fit into 14 syllables, then when you’re relaxing, you might prefer to read a haiku, or a prose poem.

(I just realized that that metaphor is only going to work for about five people, but I think I’m OK with that.)

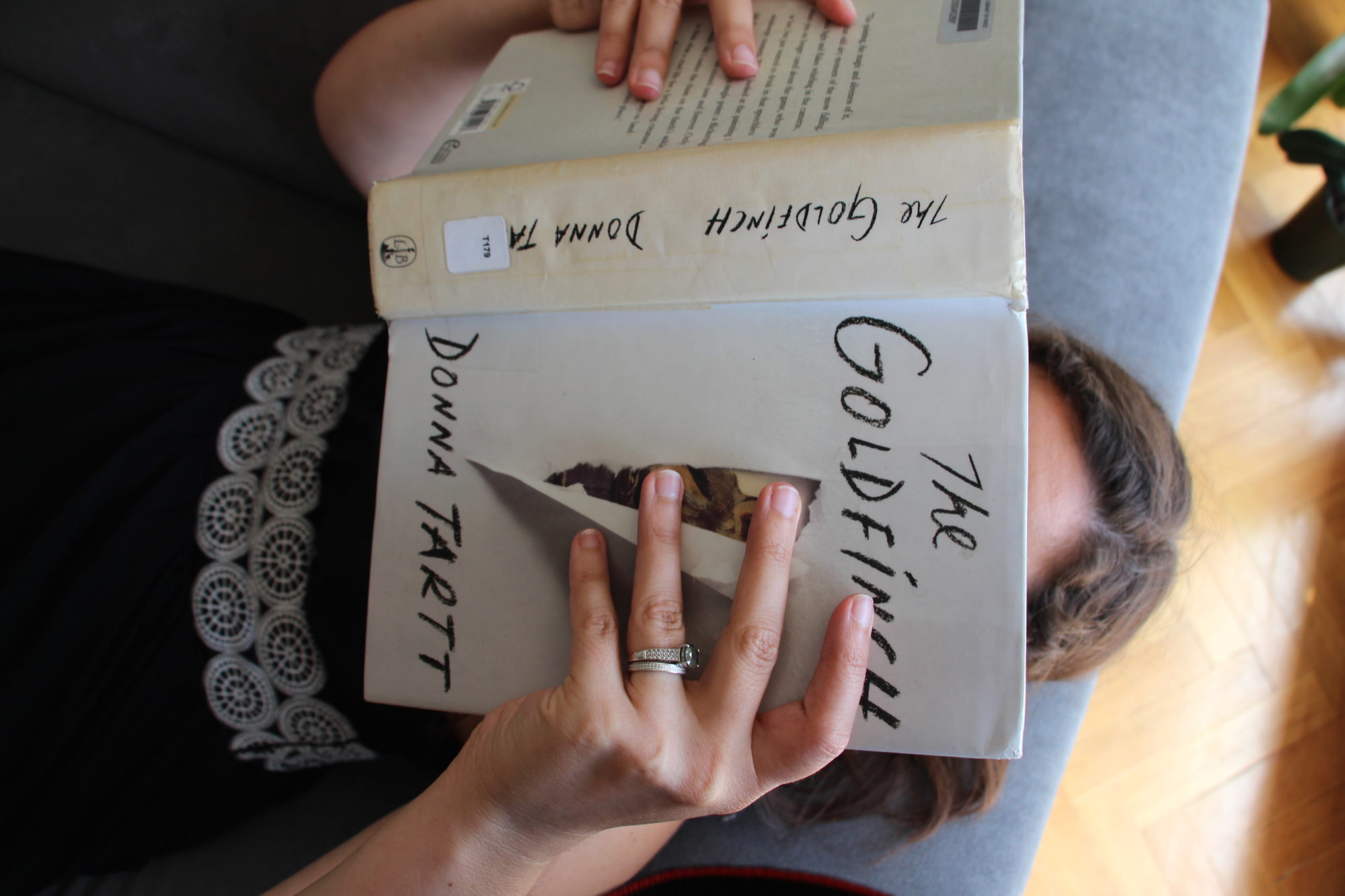

This horrendously long preamble is my way of saying that after The Goldfinch won a half-dozen prestigious awards and was recommended by everyone and their mom, I was reticent to pick it up myself. I worried that something with so much mass appeal would be formulaic and therefore that I would lose interest, in the same way that I do with most of the “you’ve gotta read this” books that have come out in the past two years.

Friends, I read those 800 pages in two days, and I loved every last one.

This book had pretty much everything I need to be happy reader. It had New York City as a background (and a believable New York, not a derivative one). It took choreography into account (one of my pet peeves is when books magic characters from one location to another or allow characters to buy things they can’t afford. I can suspend my disbelief for magic; not for economics and basic physics). It had a homoerotic ro/bromance with a stunningly, uniquely weird character that I am at once excited and worried to see on the big screen when the film finally comes out. It was pacey in the right parts and lingering in the right parts. It had just enough of that realistic, everyday magic that I love without edging into the world of magical realism or fantasy.

Oh, and it had an ending that I actually like. That’s huge praise, coming from me.

But more than any of these things, what really swept me away was the adolescent protagonist. As a reader of YA, I obviously spend a lot of time in the minds of teenagers, and I was intrigued by how Donna Tartt managed to create an adolescent voice that was at once believable and attractive to adults, rather than to teens (though let’s be honest, teen Emily would have eaten this right up). There’s something masterful in the way Tartt explored her narrative stance and found the perfect place from which to tell this story of a boy who is, throughout the book, anything but a reliable narrator, and yet as a teen is truly, heartwrenchingly innocent and naive. About 100 pages into the book, I noticed how agilely the book was circling the trope of a navel-gazing, misanthropic Holden Caulfield and masterfully creating something entirely new; it was at this point that I closed the book, looked at the cover, and realized that it was written by a woman. I was not surprised.

I don’t often buy books (The Country Boy is flipping his lid as he reads this – but statistically speaking, it’s true). I get most of my books from the library, and I actually buy a select few that I either can’t find at the ALP or that I need to own. The moment I finished my library copy of The Goldfinch, I went straight to Amazon and ordered it. This is a book that I need to have in my home.